Debunking the stereotypical ideas and media representation about Iraq and the issues that surround it is an integral part of multimedia artist, painter and curator Sundus Abdul Hadi’s work.

Sundus’s parents are Iraqi and she was born in the UAE. The family migrated to Montreal, Canada was she was about 11 years old. Art runs very deep in her family as her mother is an artist, father an architect, husband a musician, and sister a photographer. She, her husband, and her sister are also a part of a multimedia artist collective called The Medium.

Sundus’s work has been exhibited in places like Palestine, UAE, Canada, USA, France, UK and Saudi Arabia. She has also been a speaker at Nuqat, the Arab Development Initiative, the Nobel Peace Prize Forum, and at multiple universities in Canada and the US. She also hosts ‘Al Ruwad: The Groundbreakers’, a radio show about art and culture on CKUT 90.3 FM in Montreal.

Over a few emails, we spoke to Sundus about her art practice, music, education, collaborations with her sister and husband, and inspirations, among many other things. Read on:

Tell us about your childhood – your growing up years in the UAE and Canada.

I am a Gulf baby! I am a part of this phenomenon of displaced Arabs born in the UAE to educated parents during the Gulf boom in the 1980s. While growing up I never thought it was a significant aspect of my identity, because as a non-local, you’re never encouraged to call the UAE your “home”. Now I realize that being a Gulf baby is a significant experience in the changing tides of Arab identity. I think that’s partly why I was so connected to my Iraqi roots- exploring that part of who I am was less confusing than making sense of being born in Abu Dhabi but never really being “from there”. I always wished my passport said I was born in Baghdad instead of Abu Dhabi. I needed some sort of proof of my Iraqi identity and its misplaced nostalgia. The visits to the homeland became formative memories that I carried well into my adulthood, storing everything from the smells of my grandmother’s home to the “feeling of belonging” which I spent so much time trying to find again but never did.

When I immigrated to Canada with my family, I was 11 years old. It was an interesting age to transition from East to West, and I believe it was easier on me than the rest of my family. Therefore, I was the only one who stayed in Montreal while the rest of my family scattered around the Middle East. We are a family of artists. My mother is an artist, my father an architect, and my sister a photographer. All of our work is geographically rooted in the Arab world, conceptually and by way of inspiration.

Sundus Abdul Hadi

What influenced you creatively when you were growing up?

My parents were a great influence on me creatively. My mother was always creating in our home – painting, sculpting, drawing, and sketching. Because of her, we were surrounded by art our whole lives. My father’s collection of books on Iraqi heritage and Islamic art and architecture are some of my most prized possessions. I spent my university years using those books as resources for my artistic practice and art history papers. Studying art in a western institution, I was really starved of content that I could relate to, that spoke to my identity as an Arab, as an “other”. Those books started me on a journey of self-exploration through our visual culture that I’m still deeply interested in.

You did your arts education in Concordia University. How was the experience there?

I studied Studio Art and Art History in my undergraduate degree. In September 2002, on my first day of class as a young wide-eyed student, I sat in the Art History class quite nervously. The professor entered the auditorium and introduced the class by reading from a report written by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, titled “Defending Civilization: How our Universities are failing America and what can be done about it”.

The professor continued by saying that the report, endorsed by Lynne Cheney, (American author and wife of the 46th Vice President of the United States, Dick Cheney), states that universities that teach Islamic and Arabic culture and history are in fact supporting the terrorist acts of 9/11 and are sympathetic to the terrorists. I was sure that she would throw the document on the ground and say, ‘Absolutely not! That’s all propaganda!’. But to my surprise, she said, “And that’s why in this class I’ll only be teaching you about the achievements in the western art history.” I was in shock. As soon as the professor called for a break, I walked out of the class and dropped out of the course. A week later I was reading Edward Said’s Orientalism.

I struggled a lot in art school because the faculty and students didn’t engage with my work and my identity, and they were ill-prepared to deal with the socio-political issues. The war in Iraq was raging and Islamophobia was on the rise, and the professors were urging me to move away from those topics, and/or gave me stereotypical readings of my work.

Fast forward to today, I am back at Concordia University doing my Masters in Media Studies. The communications department answered all my academic needs, and I feel like I’m in an environment that supports my work and my vision. More importantly, my identity as an Arab woman is celebrated rather than tokenized or questioned.

My mother is an artist, my father an architect and my sister a photographer. All of our work is geographically rooted in the Arab world, conceptually and by way of inspiration.

How was the experience of collaborating with your photographer sister Tamara Abdul Hadi for the ‘Flight’ project?

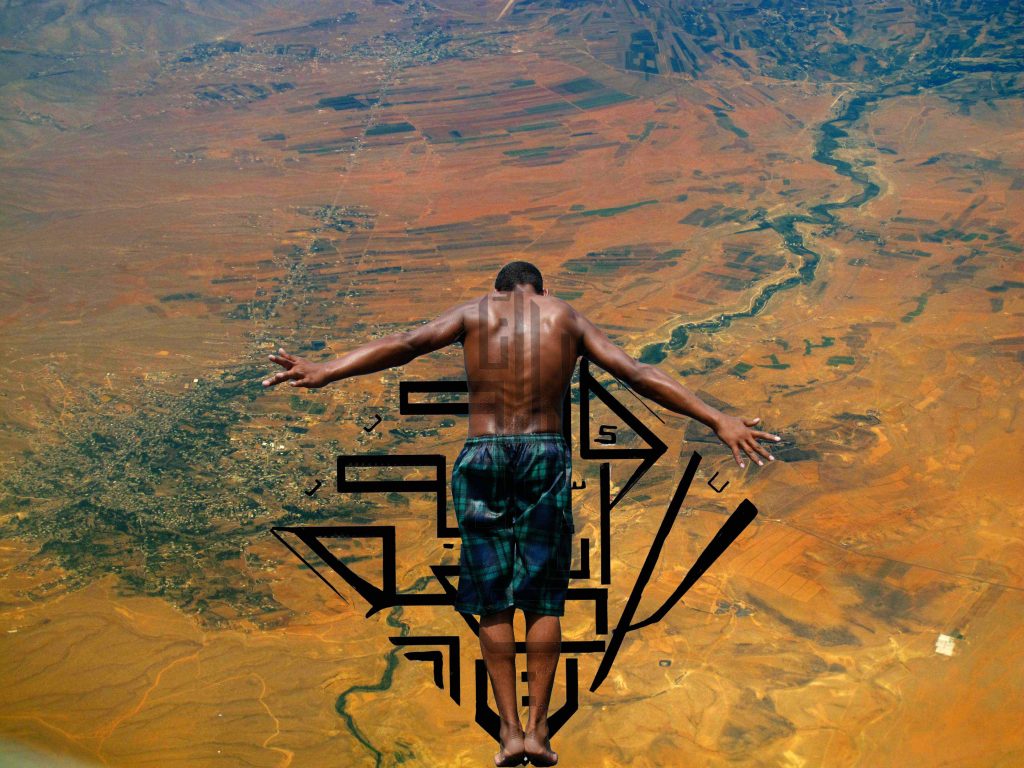

Tamara has an ongoing series titled ‘Flying Boys’ which documents young men jumping into the Mediterranean Sea along its different coasts, from Beirut to Akka. When she shared the first shots from that series with me, my imagination took flight, quite literally. Rather than seeing the boys jump into gravity, I imagined them in flight. The act of taking the figure out of their environment and transitioning them from diving to flying became a transformative experience, transporting both the figure and the viewer to an imagined space. Creating new contexts and narratives to existing images is a big part of my practice, and Tamara gave me the freedom to explore that with her powerful images.

At that time, I was doing a lot of travelling around the Middle East, capturing aerial shots from above of Baghdad to Basra, Syria to Beirut. Not having access to my studio, I started playing around with digital collages, juxtaposing the images of Tamara’s flying boys with my aerial photographs of major Arab cities and lands, sometimes incorporating the Arabic calligraphy that I had been developing. The re-imagining of these figures became a subversive tool in the context of the refugee crisis currently enveloping the Middle East, the ongoing conflicts, and the uprisings of the past decade. The underlying concept of the project is to highlight healing and empowerment in the face of struggle. Presented as a series, the works reflect a narrative geography of the Middle East and the complex issues facing the land and its people.

Fly Over Syria

From the ‘Flight’ series

Digital collage

Fly Over Golan

From the ‘Flight’ series

Digital collage

Since you both are artists, how often do you and your sister discuss work? Is there anything about her work that particularly inspires you?

Tamara’s work inspires me so much. I am simply in awe of her eye and the sensitivity with which she captures her photographs and subjects. We share our work with each other all the time. In fact, in our family we are all each other’s first critics. We are honest with each other and give constructive feedback, a nice blend of critical thought and support. There is a lot of support in the family, which is rare to find when you are an artist as it can be such an unconventional career choice and competitive field. I never take that for granted; it is quite a blessing to have that environment.

We want to specifically talk about your very interesting multimedia project – ‘Warchestra’. Tell us about the inspiration behind the project and its making.

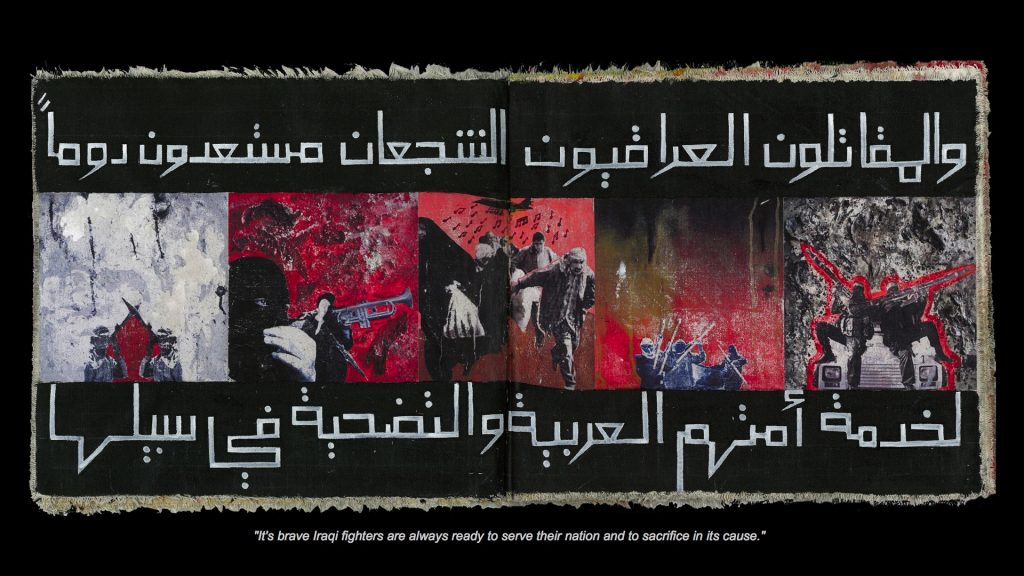

When the war in Iraq started in 2003, it took a huge toll on me emotionally. One of the ways I would cope with the confusion and grief was by obsessively collecting media images coming out of the Western media war coverage (bad coping skills). For years, I collected some of the most stereotypical, one-dimensional representations of my land and its people, and the injustice was too much to bear. I’d print the images and work with collage to reclaim them and subvert them.

Simultaneously, the environment I was living in as a young artist in Montreal with my husband Narcy (Yassin ‘Narcy’ Alsalman, a hip hop artist and educator), had me surrounded with musicians. Music and culture were a big part of my daily life and existence, along with a deep interest in Iraqi music. One day, I had printed an image of a young militant holding an AK-47, and I imagined him holding a trumpet instead. Initially, it was an act of censorship – I was sick of seeing violence. After I did that first piece titled ‘Baghdead’, I started noticing how all weapons resemble musical instruments. Have you ever noticed how similar an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) is to a clarinet? Or when it’s propped up on a militants shoulder, it looks exactly like a trombone? A five-piece Chalghi band posing for a photograph mirrors a scene from a hostage video, and violins look just like tanks from an aerial perspective. And so the ‘Warchestra’ series developed into a collection of about 30 paintings re-imagining, reclaiming, and reinventing the war in Iraq through music and culture.

Narcy and I started to work with musicians and poets to create a soundtrack to each painting, using the instrument depicted and field recordings I made in Baghdad during my last visit in 2009. ‘Warchestra’ developed into a full-length album, and the work is almost always exhibited as a multimedia experience, with both sonic and visual components.

This is Not Haifa Street

From the ‘Warchestra’ series

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

Have you ever noticed how similar an RPG (rocket propelled grenade) is to a clarinet? Or when it’s propped up on a militants shoulder, it looks exactly like a trombone?

Since music is an integral part of ‘Warchestra’, tell us a bit about what kind of music do you really like in general?

Music is my first love. Before I started painting and drawing, I played piano for a decade. I wish I continued that, but alas, I quit after a series of moving countries from the UAE to Canada and back again. I’m a digger. I love Arabic music, but not mainstream pop. I love the classics, hip hop, R&B and soul music. I also love the new exciting music coming out of the Middle East and I love when both the East and West blend into one another through sonics, like when artists use quarter notes (unique to the Arabic scales) on Western instruments. Baligh Hamdy was the king of that. My cousin Sandhill (Nawar ‘Sandhill’ Al-Rufaie) is a pioneering Iraqi producer, and every beat he makes is gold to me, especially when Narcy spits on top of them.

You also host a show called ‘The Groundbreakers’ on radio right?

Radio is truly my favorite medium to work with. I’ve been doing radio for eight years now on CKUT 90.3 FM in Montreal, a community station. For the past few years, I’ve been hosting and producing ‘The Groundbreakers’ every Wednesday, featuring pioneering art, music and culture from the “other” world. Choosing to focus on the achievements of people of colour that have been doing groundbreaking work is so empowering to our communities. I often feature interviews with musicians, artists, authors and activists from around the world, which I love doing. I’ve had the opportunity to talk to some of the most groundbreaking people alive, from Suheir Hammad to Emory Douglas. My DJ sets are eclectic, spanning across generations and geographies.

For years, I collected some of the most stereotypical, one-dimensional representations of my land and its people, and the injustice was too much to bear. I’d print the images and work with collage to reclaim them and subvert them.

You did a large scale artwork called ‘Battle for Sumer’ after your visit to Iraq in 2004. Was that the first time you visited Iraq? How was your experience?

I mentioned nostalgia and obsession earlier. It’s safe to say that those were the two most prevalent emotions connected to Iraq throughout adulthood. I spent many holidays in Baghdad as a child, but my first time there as an adult was in 2004. I guess that’s when I first realized that in fact I don’t belong there, no matter how connected I felt to my homeland. I was the “ajnabeeya” (foreigner). I honestly tried so hard to fit in but people could spot me from a mile away!

The content of my work was focused on Iraq for a very long time. Only after my last trip in 2009 did I snap out of my nostalgia and romance, and started to see Iraq as quite a hostile environment, one in which I had no place with my sensitive hyphenated identity. I left quite traumatized and anxious, and it took me many years to come to terms with this new relationship I had with Iraq, and to work on neutralizing it.

I recently completed an illustrated book called Shams which is loosely based on that experience, but re-imagined through magical realism. Shams is a little girl made of glass, and one fateful day, she breaks into a million pieces. The book follows her journey as she puts herself back together again with the help of her own imagination and the guidance of Shifaa who is a healer. A story of trauma and human resilience, Shams is a timely tale set in an unnamed Arab city, meant to empower the survivors of an abnormal experience, whether political or personal.

The Battle for Sumer

Acrylic on loose canvas

How does Montreal as a city inspire you and your work? What do you like and dislike most about it?

I hate winter but I love Montreal. It took me a long time to love this city because the nostalgia of going back to where I belong was really strong in my Iraqi DNA. After a lot of soul searching, I came to accept the fact that not belonging is okay and actually, I may never belong anywhere in the way that I was expecting to. So Montreal is home, for now, and I can be here with the rest of the immigrants who chose to adopt this land where no one truly belongs but the resilient indigenous people of Canada.

Who are the visual artists/illustrators around the world that you really admire?

I really love Emory Douglas, the former minister of culture for the Black Panther Party. As I write this, one of my paintings is exhibited next to his at the exhibition titled ‘Iconic Black Panther’ in Los Angeles – a real highlight of my career. I also love Banksy, but I also hate him for taking all the credit for a lot of subversive images I had done first (great minds think alike, as the saying goes). Laila Shawa is one of my favourite Arab artists and she made me realize that I can be my authentic self through my work.

What are the other things, amongst say books, films etc., that have deeply inspired you?

Edward Said is my homie. I love him, what he stood for, and all his incredible contributions to critical thought, cultural studies and academia. I generally love reading, and my books are some of my most valued possessions. I have everything from pioneering Arab fiction to obscure exhibition catalogs that I have collected over the years. One of my favorite books of all time is The Sense of Unity: The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture which is much more complex than the title gives away. It has been a reference for me throughout my practice.

I Love(d) Baghdad, 2-page spread

Artist Book

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

The content of my work was focused on Iraq for a very long time. Only after my last trip in 2009 did I snap out of my nostalgia and romance, and started to see Iraq as quite a hostile environment, one in which I had no place with my sensitive hyphenated identity. I left quite traumatized and anxious, and it took me many years to come to terms with this new relationship I had with Iraq, and to work on neutralizing it.

What’s on your mind these days?

I’ve been thinking a lot about the whole idea of self-care. Moving away from the more individualistic aspect of it, and looking at it more as a necessary community act to heal. If we were all taking care of ourselves, there would be less anxiety, less fear, less violence in our world. I’m a mother of two young children, so my days are spent taking care of them, and making sure they have the right tools to make it through in this crazy, unjust world.

What are you currently working on?

I’m currently in the process of curating an exhibition titled ‘Take Care of Your Self’, which is also the research-creation project of my Masters degree. It’s about the intersectionality of struggle, bringing together works by different communities of color in an exhibition/intervention in self-care and collective empowerment. I’ve been thinking a lot about how trauma and loss have affected the different communities I am surrounded by here in North America, specifically the Arab/Muslim, Black and Indigenous communities. There is a collective grieving happening in those intersections, and I’m trying to move the focus to a collective healing through this project. I’m really excited about this project. It will happen in Montreal and Toronto this summer.

I’m also the co-founder of We Are The Medium, along with my husband Narcy. It’s a platform where all our creative ideas get funneled and produced including ‘Take Care of Your Self’. Collaboration happens on many different levels in our collective, which is made up of many incredible artists from our global community. There is always stuff going on, and I often find myself working on a number of projects simultaneously.

Finally, I am hoping to get my illustrated book published and distributed. The ultimate goal with that project is to get it to the youth in refugee camps across the Middle East, struggling with their own trauma and displacement. But basically, it’s for anyone who needs to know that survival is within us, no matter how broken we are.

Choosing to focus on the achievements of people of colour that have been doing groundbreaking work is so empowering to our communities. I often feature interviews with musicians, artists, authors and activists from around the world, which I love doing.

Descend to Ascend

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

You can read the rest of the issue three here.

Sundus Abdul Hadi’s image is provided by her. ©

The cover artwork is Rumanna. Images in this work are taken from Tamara Abdul Hadi's photographs. ©