This is a great catastrophe. This is not something to be taken lightly. The amount of people who have lost their jobs, their homes, their health insurance, and who don’t have any safety net to hold them, is staggering. I hope that at least some of us have taken this time to reflect and realize that we simply can’t go on like this. And I think going forward, we will need each other even more.

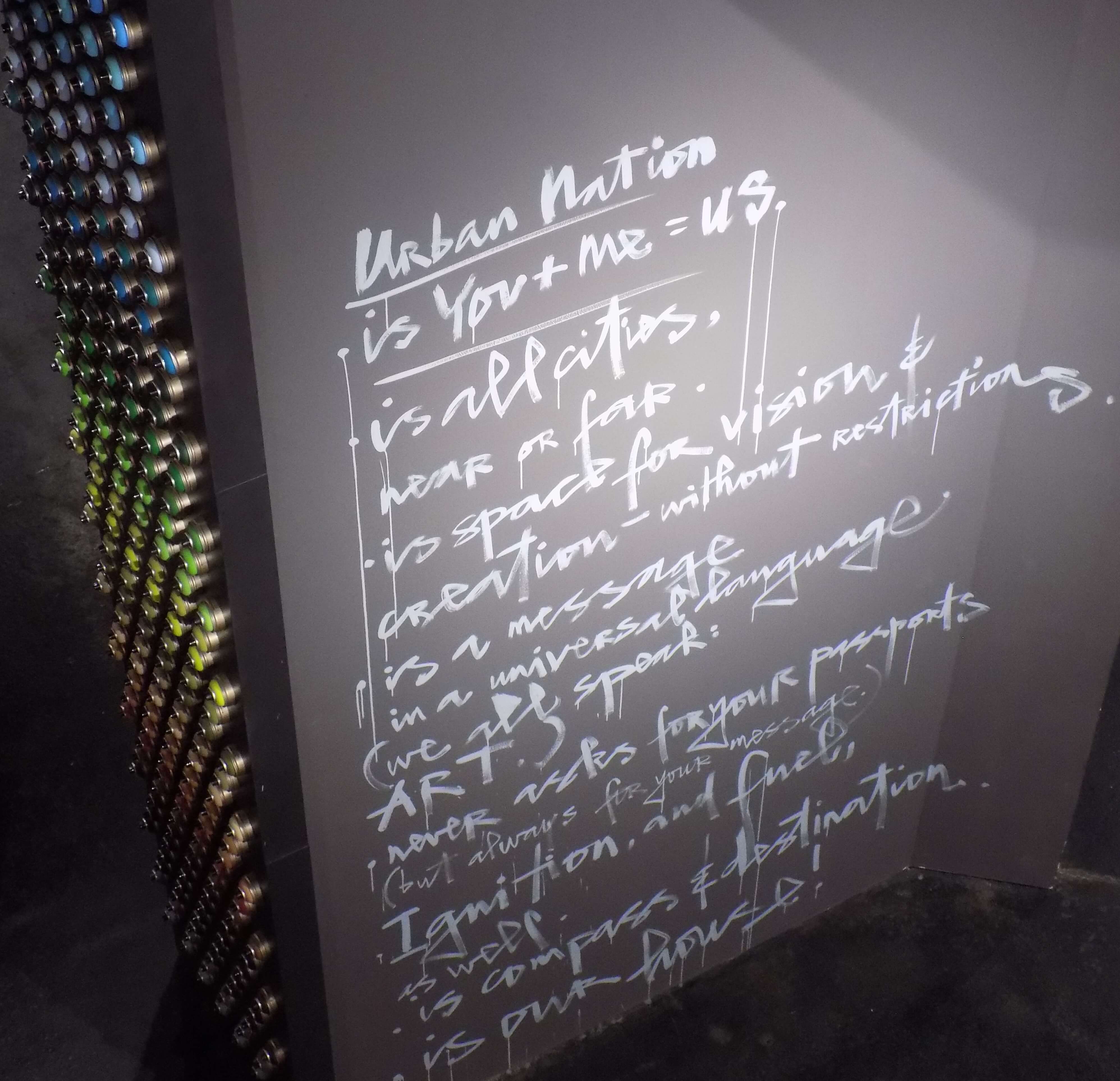

Yasha Young is the founder, concept creator, and executive creative director of URBAN NATION, Berlin’s first museum dedicated to street art. Yasha has also created two other key art projects called Project M/ and ONE WALL and an artist residency program for urban contemporary artists called Fresh A.I.R.

Yasha has been a part of the international art scene since 2001. Before URBAN NATION, she launched and managed Strychnin Gallery, with locations in NYC, London and Berlin, from 2001 to 2013. She has curated more than 250 exhibitions all over the world with Shepard Fairey, Swoon, Invader, Sotheby’s UK, Omotesado Hills Tokyo, Saatchi UK, Lollapalooza Berlin, Museum of Contemporary Art Rome, among others. She is also the co-founder and director of Blooom Award for emerging artists.

On a New York morning and Mumbai night in August, we had an inspiring conversation with Yasha over Zoom about URBAN NATION, her various other projects over the years, creative influences, collaboration, and how the pandemic has influenced her and her work. Read on:

Yasha Young

Could you tell us about some of your early life experiences which led you towards art?

I think the earliest memory that is relevant to my creative development is the time when I went to London as a teenager. It was my first experience of seeing a very vibrant city that still had this punk rock vibe. Everything was so colourful and moving. And there was this very rebellious energy which was amazing for me to experience. I would just absorb all the colours in the streets, the red buses, people from all over with their distinct dressing styles, and the smell of Indian food at Brick Lane. That’s probably the first thing that was important to my development as someone who sees art in everything on the street.

In London, I also met people who were much older than me, and for them, this was a natural way of living. I didn’t understand punk rock music so much at that time and learnt a lot about it from those people. They would show me albums, explain certain songs to me, and even took me to places which I should never have gone to at that age! (laughs)

Most of what I have learned was not in school, but from people around me. And then I became that person who wanted to pass things on to the next generation.

How did you end up launching your own art gallery – Strychnin Gallery?

I came to New York by myself when I was quite young and lived a proper immigrant life, with no money but big dreams. I would sleep on the floor in a basement apartment in Manhattan. And I learned really fast that you have to hustle to survive and make things work.

Then I went to The Lee Strasberg Theater & Film Institute while working in a restaurant on the side. And again, because of my experiences in London and the people I knew there, I formed connections here easily. So it was always about people, some of whom ended up introducing me to the art gallery and the underground art scene in Manhattan. I was so fascinated by it all.

After I got a job at Wilhelmina Models, I started saving money and continued to stay very close to the art world. Around that time, artists would often say, ‘Man, nobody wants me in their gallery because I don’t sell work yet.’ And I was like, ‘Okay, let’s find a space and open a gallery’. So it started out as a sort of movement for friends.

We had all these art salons happening in big lofts (which people could still afford at that time), so there was a lot of beautiful work everywhere. We initially also did pop-up shows in different artists’ lofts. And that’s how I slowly started to learn how to curate. I learnt what it means to interact with your audience; what does a buyer actually want; and how does that entire network works. We also had support from quite a few successful artists at the time. They would often offer a piece of work for the exhibitions which would help us get a new audience. That’s how it kept evolving.

Was starting a brick and mortar gallery overwhelming for you in any way?

I am lucky to have grown up in the generation which was always like, ‘You want to make a magazine? Let’s make a magazine. You want to do an album? Let’s make a record.’ We all had this ‘let’s do this’ attitude. And I loved that spirit. Opening a gallery happened quite organically for me. It wasn’t without its struggles though.

After I opened the gallery here, I went on to open one in London and then in Berlin. And all of this required a huge amount of sacrifice. If you decide to do something like this, you have to know that this will consume your life. To prepare for one show a month in one of the locations, there are just too many things to take care of and you have to put your personal life on the back burner. There is so much travel involved. You start living and breathing your work. Fortunately, I liked doing all of it.

The decision to shut the galleries to work on URBAN NATION must have been quite heartbreaking for you.

While I was running my galleries, I was asked to become the creative director of this art fair in Cologne (now called Art Dusseldorf), and I said yes. That was a lot of work. Imagine curating the galleries and their programming as well as running an art fair and the publicity for it – all at the same time. But I got to learn another side of the art business through this experience. My wish to create a bigger space and develop something different from the ground up in service of artists bloomed from there. This is when I started writing the concept of URBAN NATION, and it took me several years to develop the concept. Then when I got asked by a social housing group in Berlin if I had an idea for a creative project, I said, ‘Yes, I do. Do you want to build a museum?’ And fortunately, they agreed.

Then, of course, there was the melancholy of knowing that I needed to shut down the galleries to be able to focus on this. Even though it was melancholic, I was fuelled by the energy of wanting to create something new. And when I look back today, I am grateful that all of this happened. Would I ever want to open and run another gallery? Probably not, but who knows. However, I do not regret a single day while I was running my galleries. Everything I learnt and everyone I worked with or met during the process helped me create URBAN NATION.

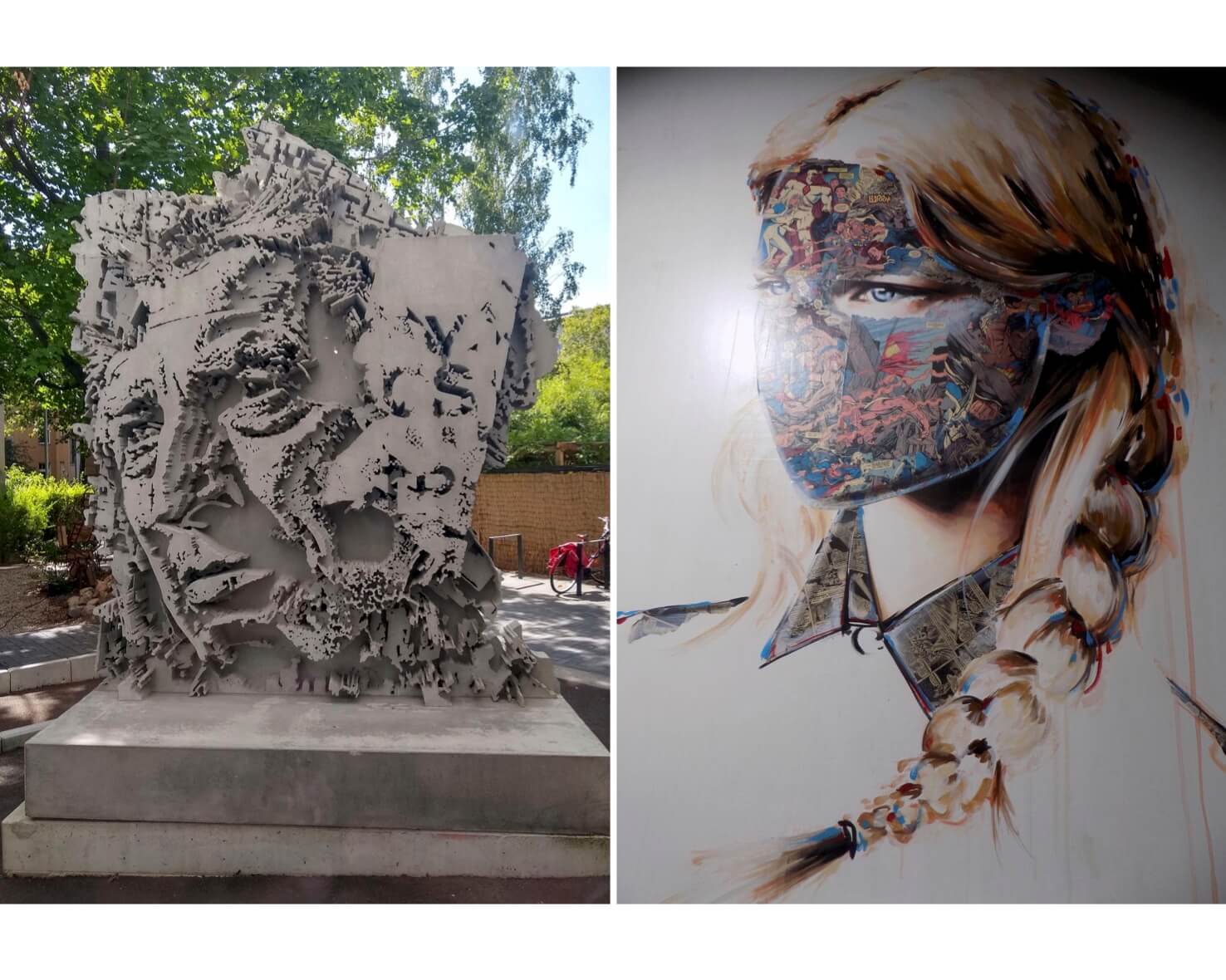

URBAN NATION, Berlin | URBAN NATION photos by Payal Khandelwal

Artworks by Vhils (left) and Sandra Chevrier (right)

I am lucky to have grown up in the generation which was always like, ‘You want to make a magazine? Let’s make a magazine. You want to do an album? Let’s make a record.’ We all had this ‘let’s do this’ attitude. And I loved that spirit. Opening a gallery happened quite organically for me. It wasn’t without its struggles though.

How was the initial experience of launching URBAN NATION?

It was all very exciting right from the beginning. I was going to be able to build a big platform for artists that involved working with them in a medium that I loved – street art, and create a space that would tell the history and story of the people behind the works on the street. Moreover, this would be an international project featuring artists from all over. Actually, the excitement of building new things and progressing in the art world has never left me.

The challenges were in terms of what it actually takes to do this. While I had the concept, support, and location, it was not the house it is today. I needed to find an architect and conceptualize the design of the house, which I wanted to be very innovative and functional. And at every step, there needed to be budget discussions and fundraising. There were so many entities involved – city officials, artists, neighborhood. Even before the launch, I wanted to activate the house so that people would know what was happening there and start becoming a part of the process.

Most of the people executing the project were not from the art world and were constantly changing. My core team was just two people. So you become like a spider in the middle of the web, trying to hold it all together, trying to see where the web is moving. That was probably one of the biggest challenges to consider.

But I knew exactly what was inside my head, and I had to hold on to it and stay true to my vision throughout the process despite all the challenges. And if somebody told me an easier route to do something, I had to firmly say no. I believe that you can’t take shortcuts because every shortcut will come to bite you in the butt later. In a project like this, there are all these little chains interlocked with each other, and the minute you start taking a sideway, the whole chain will break.

Did you ever get questioned about the decision to keep the museum free?

Yes! A lot of people, especially people who were involved in the investment, constantly asked me why this is free. The point is that it wasn’t my house to begin with. I wanted to build this for the artists and the community and even they had to be involved in taking care of the house. All the artists made huge initial investments in terms of their work. We didn’t have the money to pay them initially.

In the beginning, people still didn’t question the museum being free because they thought this was a crazy idea which won’t really work anyway. But when they realized that the idea works – 65,000 people came to see the opening – they were like, ‘wait a minute, if we charge $5 or $10, that would amount to a lot of money’. But that would have defeated the purpose of the museum. I wanted it to be democratic. For example, we have so many groups of school kids that visit the museum because it’s free as they don’t have the funds to pay for a museum. And if they have to pay, they would have to choose a traditional gallery that fits their syllabus over URBAN NATION.

So this was one of my biggest requests that anything and everything we do is funded and is a donation from culture, for culture. I think this was the only way for it to be democratic.

In your TED talk, you have spoken about the importance of art to create a dialogue instead of being a one-way street. This seems more important now than ever. How do you feel about this currently as a curator?

I consider myself an activism curator. For me, it is extremely important that everything I curate is in one way or the other connected to some deeper meaning, cause, or reason. I believe that I have the responsibility to be a social documenter or a spokesperson for what’s going on in the world around me like the #BlackLivesMatter or #MeToo movements.

Through these movements, we have seen so much art in the form of protest signs. Art can be a crucial means of communication. It can transport messages without relying on any language. I keep saying this over and over again – if you write the word ‘flower’ in a particular language, many people will not understand. But if you paint a flower, everybody in the world will know it is a flower. So for me, art is a language and it needs to be used for the greater good.

Another thing I want to talk about is collaboration, which is a massive part of your work. While collaborations are great in general, are there any particular challenges you have faced?

What kind of collaboration are we talking about?

Let’s say a collaboration between you as a curator and an artist. Where do you draw the line if something isn’t working out for you?

I think it starts with the choice of your collaborative partner. You will probably not collaborate with someone who is being extremely difficult right from the beginning. But sometimes you do end up getting into partnerships that turn difficult over time. And they both need to understand that compromise and an enormous amount of respect for each other’s work is part of the process. Of course, it’s also very important that neither party feels that they’re going beyond what they’re willing to compromise.

I will draw the line, for example, when I feel the people I work with have become unhappy because of the partnership. Or if there is verbal abuse involved, or there are massive creative differences.

Screenshot: Yasha Young: The Shift of Contemporary Art | TED Talk

Left: Yasha and ELLE working and planing in her studio in NYC | Top Right: Yasha and German Ambassador Herbert Beck in front of the Telmo Miel Mural in Iceland for her project there | Bottom right: Michael Mueller, the mayor of Berlin and Yasha opening the UN Biennale | Photos courtesy Yasha Young

We need a system where we use technology to further humanity and not the other way around which is to use technology to dumb us down!

Another thing you’ve spoken about in your talk is how some street artists end up becoming brands eventually, working for corporates. How, according to you, can an artist create a balance between doing something they are passionate about and making big money?

Well, it’s a very individual decision. It depends on the artist. Some artists are very business savvy, and they balance themselves really well. It also depends on where you are in your career. When you’re in your mid-to-high level career, you have an easier time saying no to something than when you’re just starting out.

I think responsibility with money is a very big thing because money is very tempting, especially for creative people and understandably so. It’s just a question of how far do you push yourself or what is it that you really want?

Some artists strive for something different, but they have to survive as well. And this is when the negotiations become interesting. Who do you actually partner up with? Could that be good for your brand? And then there are those combinations where later when you’re an activism artist, people might say, ‘Yeah, but you took 50,000 euros working for an oil company when you were 21.’ So you have to just think about these things.

Why did you decide to leave URBAN NATION as the director in 2019?

I was headhunted by another group who wanted to build a new museum. They asked me to write a concept for them. There will be two museums, one in Europe and then this one, TheFor.M.

I was interested in having the opportunity to step outside. I created URBAN NATION, the UN Biennial, the artist residences, etc. So all that’s done. It’s a whole package. If I ran all of it more than I did, it would be a bit of waste of my creative energy. Of course, I’m going back there probably for the next UN Biennial to curate again, and I will always have an eye on what’s going on. But I think it has to carry itself now. Museums are only as good as the people who run them, and I just hope and pray that the person running it now understands the mission and runs with it.

But for me, I needed to progress and challenge myself. I’m presented with quite some challenges right now, just like the whole world is, but I also see a great opportunity here to see how we will evolve as humans. What role would art play during this time? And how can we incorporate this into new concepts? Visitor behavior has changed as well, and will probably remain changed forever. Which institutions will still remain open; which collections will be destroyed? It’s going to be such a horrifying but also a very interesting time.

Would you be willing to talk more about the current project, or is it under wraps?

It is under wraps. All I can say is that creating URBAN NATION laid the foundation for it as I learnt so much from it. I also realized that I could do more and better in order to grow with a fast-growing, highly demanding audience. I am also teaching at the university POP ACADEMY, Mannheim and studying at Harvard University for my research on museums of the 21st century. So I am ready to do a project that will use all of my learnings.

Could you tell us about the ‘ONE WALL’ project? How did it start and are you still doing it?

The ‘ONE WALL’ project started because I wanted to focus on one wall, one neighborhood, and one artist. With this project, I wanted to take the speed element out of the creation. I wanted to slow down the process and do one wall with one artist for like ten days. This helps us to understand the process so much better. It helps you as a curator later to gauge the capability of the artist. What do they really want to do and how can you create something with them which explores their full potential? When you slow down, you also get to know and engage with the neighborhood more.

I hope we are able to continue doing this when the world recovers. However, right now, I don’t think painting huge walls should be the focus. I think that the art budget should be allocated to online art classes for kids. There should be art programs for senior citizens who are the most vulnerable in our society and often the most lonely.

I was locked for two months alone in my apartment in New York. One of the things I’ve learnt through this confinement is that I would want to use whatever budget, time, and art resources I have to solve the problems and ease the situation of those who are suffering. I see this time as something where we go back to the beginning and use art as a means of communication for those who cannot communicate for themselves and as a tool to bring society together.

ONE WALL projects Top Left: By Nils Westergard | Top Right: By Francisco Bosoletti & Young Jarus |Bottom: By D*Face & Shepard Fairey | Photos by Payal Khandelwal

ONE WALL by Don John / Berlin, Germany | Photo Courtesy Yasha Young

Yasha Young

Are you based in New York or did you have to stay here because of the lockdown?

I live between New York, Berlin, London, and Munich. I travel a lot and my original home base is in Iceland, that’s where my people are from. I am a gypsy though, which is interesting at this time because I’m so not used to being in one spot and separated from everyone for so long.

The one thing that’s most important in our nomadic art form, street art, is that everybody travels all the time. And at this time, all of us have to deal with being static. But I think it has been good for a lot of the artists because it brought them back to their studios to really focus for a longer period of time on creating canvas work, prints, etc. And this could be taken as a positive.

How have some of the artists you know reacted to this time?

I think we’re seeing the full spectrum. I see a lot of people get very involved in their work and that is their way of dealing with this confinement and frustrations about their own situation. I’ve also seen some people who have taken a step back to think about the changes they want for themselves. Then I’ve seen quite a few people suffer through this or be very scared of the future and understandably so. There are also people who have excelled, reinvented themselves, become really creative, and used the spirit of the fight or flight response. It is all very individual though. I can only say that I literally had everything on the spectrum within my circle of friends, and I tried to be as supportive as possible.

For myself, I really had the whole spectrum inside me. I was going from ‘what a great opportunity to grow’ to ‘oh my god, this is all going down’ to ‘what the hell is happening’ to ‘let’s do this’.

Top left: URBAN NATION | Top right: Mural by Don John in Reykjavik, Iceland | Bottom: Yasha Young | Photos courtesy Yasha Young

One thing that’s most important in our nomadic art form, street art, is that everybody travels all the time. And at this time, all of us have to deal with being static. But I think it has been good for a lot of the artists because it brought them back to their studios to really focus for a longer period of time on creating canvas work, prints, etc. And this could be taken as a positive.

Have you had any thoughts about your role as a curator during this time?

This time has definitely enhanced my perception of what a curator should be. It has made me more aware that just curating pretty pictures will never be enough for me. In fact, I think we need to teach about history along with art now more than ever. We’re about to have a recession, one of the worst in history, and we have to learn from this. My focus on being an activism curator – to become part of the social change and to raise awareness of the issues that the world is facing – is going to be even stronger now.

Approaching new concepts is also interesting for me. I don’t believe in going completely virtual as we still need one-on-one interaction with art. I still believe in the ‘human factor’, something I had mentioned in my TED talk too. People need to connect one-on-one with each other, and the artworks need to be experienced in person.

The laws of physics or things we know have shifted and have taught us now that we all have nothing but our fellow humans and that at the end of the day, we’re still acting on the innate principles of Neanderthals. We have a pandemic and the only way of defending ourselves and what we have for protection, considering all our technology, is to stay home. Think about that for a second! And then you realize that we still know nothing. But it doesn’t mean we can’t do anything. It’s just ironic that the only way to protect ourselves and all our great accomplishments is to close the door and stay at home. But I think as we emerge from this, our ideas of collaboration will become even stronger.

So you feel that post Covid-19, people will need more human, one-on-one interaction with each other?

I think so. I think people have experienced extreme loneliness during this time and many of them have had to focus on themselves for the first time. And I can only hope that we have learned something from this because we couldn’t distract ourselves anymore. I think even the most hardcore Instagram users also got bored eventually. But Instagram was a great platform to see how low our society actually is as a whole. I think it was very interesting to see that at one point the content completely went from being creative to being completely delusional and weird. And that also shows that there’s utter helplessness on how we move on from here. Is there a new way to find our way?

This is a great catastrophe. This is not something to be taken lightly. The amount of people who have lost their jobs, their homes, their health insurance, and those who don’t have any safety net to hold them, is staggering. I hope that at least some of us have taken this time to reflect and realize that we simply can’t go on like this. And I think going forward, we will need each other even more.

Another takeaway is in terms of education. I fear for the generation of young adults that is now graduating and immediately going into joblessness or the kids who have pretty much lost a whole year of school. Not every kid is capable of catching up or seeing staying at home as something fun. A lot of kids might be traumatized because they can see that their parents are under a lot of stress.

And although this is the US, when the outbreak had hit, there were places where people had no access to the internet. To me, this is something unfathomable – how can we not find ways to help our youth to learn. I understand the necessity of the complete lockdown at that point, but how are we going to do this in the future. I think this is a real opportunity to rethink our education system. For example, there’s this school in Germany, where a friend of mine is teaching, that splits the classes into very small groups which generates more space and more focus. And the classes are further split into one-on-one offline and online sessions. So we need a system where we use technology to further humanity and not the other way around which is to use technology to dumb us down!

I also want to do projects in hospitals. All of us are now using masks regularly and it has shown us how much we need expression and smile, especially in a hospital environment where people are already so vulnerable. I want to figure out how we can use art in places like these to make the environment slightly better, to encourage healing and improve mental health and comfort for people there.

I know this is a lot of information. But if you ask me what I have been thinking and how I would like to go forward, these are the subjects I want to work with.

All images are copyrighted and cannot be used without written permission by respective image owners. ©