In 2018, it was the fight of our lives and we had no option but to win. And I say ‘we’ because it was a collective pain.

Sofia Karim had to dismantle the world as she knew it and start remaking it in the year 2018 after she received a phone call.

The call was about her uncle, Shahidul Alam, a globally renowned photojournalist, activist and teacher from Bangladesh, who was arrested by the police and subsequently kept in jail for 107 days. He was charged for the “provocative comments” he made in an Al-Jazeera interview, under section 57 of Bangladesh’s Information Communications Technology Act which Human Rights Watch have called a draconian law. Apart from being a loving niece who had spent some of her most important and beautiful childhood moments with Shahidul, Sofia now had to, well, fight for his life. She became one of the key campaigners of the ‘Free Shahidul’ movement that slowly started gaining momentum in various parts of the world and got a confluence of famous creatives and common people together. The fight to free her beloved uncle propelled Sofia into this new world she started creating.

This new world, the way I see it in her work and through our conversation, is creative, poignant, and makes us look at things we identify with in a completely new way. It knows what it seeks. It embraces collaboration. It demands accountability. It calls for direct action.

Sofia is an architect (practicing for over two decades), an artist, a writer, an activist, and also a poet. I have added ‘poet’ because poetry – as well as profound passion – pervades throughout my entire conversation with her and in her work. In fact, all of these identities often merge together in most of her projects – ‘Turbine Bagh’, for example.

‘Turbine Bagh’ is a project inspired by the Shaheen Bagh movement in India, a powerful and peaceful women-led resistance movement to oppose CAA (Citizenship (Amendment) Act) that threatens to brutally demolish the secularity that India has lovingly and carefully built over the years. The rampant fascism in India bothers Sofia a lot, and she finds a lot of commonality between the governments of Bangladesh and India in this context. Sofia decided to become a part of the Shaheen Bagh movement in her own unique way through ‘Turbine Bagh’ – a reference to Turbine Hall (at Tate, London) where she was planning to hold a protest in support of the movement, which was unfortunately postponed because of Covid-19. It, however, manifested itself into an Instagram account where artists from all over the world submit their work on various important causes. Turbine Hall, of course, also happens to be the site where one of the key protests for Shahidul Alam took place in London.

In the living room of her home in London, where she lives with her husband and two kids, she comfortably settles down on the floor in front of the sofa, with a poster of Chobi Mela above it, when we connect through a video call. We talk about her childhood memories, Shahidul, her reinvention of architecture, creating work from imagination and memories, the impact and importance of Shaheen Bagh, the unique world of ‘protest art’, among many other things.

Sofia Karim. Photo by Lylah Sanderson

What are some of your childhood memories that have stayed with you?

One of my strongest childhood memories is a flock of birds suddenly darting through the sky, a kind of grey lead sky, and the fact that I was alone in the UK without my parents suddenly dawning upon me. And the second very strong memory I have from my childhood is looking down at my arm whilst I was playing on a swing, and realising that my skin was brown, not white.

In terms of the structure of my upbringing, I was born in the UK. My very early childhood was spent in Libya where my parents were working as doctors, and then we came back to the UK. So I have lived in London almost my entire life.

What were some of the early creative influences in your life that nudged you towards art? And how much did your uncle, Shahidul Alam, influence you creatively when you were growing up?

Apparently, I used to communicate through drawing before I could talk. That’s what my parents tell me. My parents actually had very little interest in art and there were no art books or works of art in our house. If anything, I too tried to suppress my interest as I grew older, because my parents didn’t want me to practice art. But at the same time, I had seen my mother make everything by hand, including my toys. Even though she has no art background, the grace and beauty of her line is something I still envy.

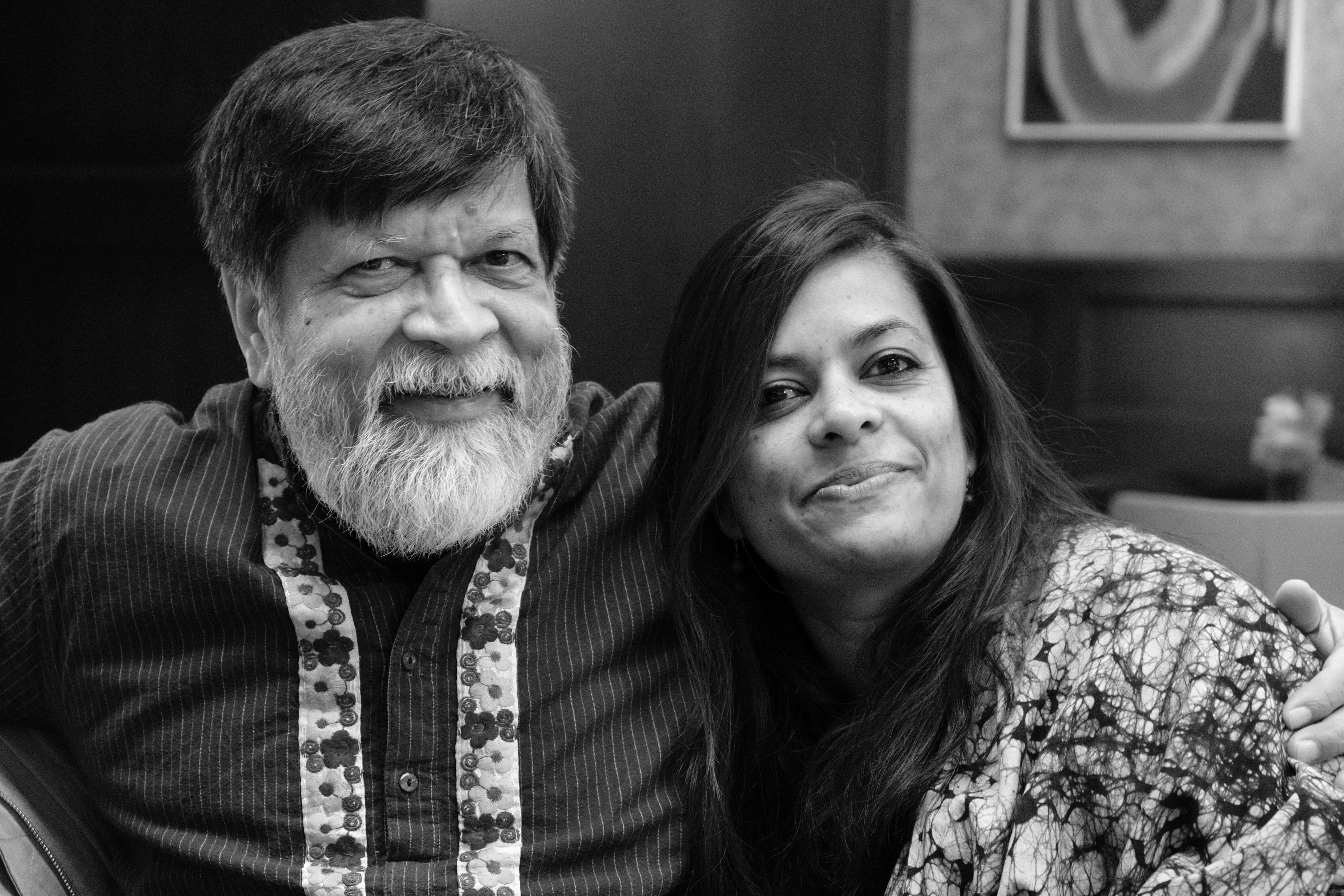

Shahidul was a huge and fundamental influence on my upbringing. I want to talk about that on a human level first. What he brought was a sense of freedom and exhilaration to what was otherwise quite a suffocating and depressing existence for my sisters and I growing up as immigrants in the UK. We had a very strict upbringing, which had caused us to be quite shy and inhibited as children. And the fact that our parents were so strict and not so happy was really a reflection of the pressures they themselves faced while growing up in this country. Shahidul really lifted all that.

I actually can’t describe what it’s like to be around Shahidul for anyone, particularly for a child. It’s something elemental. Being with him almost takes being alive to a different level. You’re lifted to somewhere higher than the ground plane of the earth. And from that place, you dare to break and unlearn everything you thought you understood, rebuild it, and break it again. He’s also the kindest man, so you feel very safe when around him. Both Shahidul and my aunt, who is a writer, have this force. They were more progressive than anyone I knew. I watched them living out their principles from a very young age.

Shahidul lived in London for 12 years when I was a child, and this was before he became a professional photographer. He would take my sisters and I along with him wherever he went – work meetings, cultural events, exhibitions, student parties. It was like if you want to meet Shahidul, you have to put up with his nieces. He would allow us to participate as equals. And he didn’t separate work and personal life as usually happens in the West. We were his shadows, immersed in his world in the most natural and fulfilling way possible. That was really my introduction to art and the art world.

Sofia and Shahidul, New York, November 2019. Photo by David Gonzalez

Could you tell me about your beginnings in architecture? How did you decide to pursue it and what were the initial years like when you started working?

During one of my school holidays, we visited Bangladesh and travelled by boat to my father’s village, not too far from Dhaka. And I went inside my grandmother’s house in the village and these are very earthen buildings. I remember sitting on the bed and watching the play of light as it entered the room. The light stole its way through a woven bamboo screen. It passed through wood smoke that was in the air, and then it hit the earthen wall. I believe it was at that point that I understood I wanted to be an architect. During that same trip, someone took me to see Louis Kahn’s Parliament building in Dhaka. I still don’t remember who took me, but I definitely remember the power of that building.

Studying architecture was immensely rewarding but it also almost drove me mad. Especially during my postgraduate degree, I suddenly felt so out on a limb and couldn’t fit in. I was convinced I was going to fail, but then I went into a zone and pushed a lot, and surprisingly, ended up winning the faculty medal. I don’t see it as any kind of mark of achievement or anything; I’m just saying how random things can be in the life of an artist.

I then started working at Norman Foster’s and learnt a huge amount there. It was excellent training involving a lot of rigour and high standards. However, it was there that I gradually began to find many aspects of commercial architecture inherently problematic and questionable. I realised that most of our built environment is actually architecture as financial speculation, and thus, these buildings are devoid of spiritual meaning and are desensitised. What you’re mainly creating are not even buildings, but adverts for buildings, not architecture, but adverts for architecture.

I think many young architects start out with a quest to reach the inner meaning of architecture. And that is cultivated in the architecture studies because along with architecture, you also study philosophy, poetry, and you’re encouraged to reach deeper and deeper. Young architects work with intense passion and dedication to their craft, and many of them do have social values and hope to serve society with their art. However, usually when they enter the world of commercial architecture, all that is killed. Now, the architect must serve a ruthless drive to maximise the developer’s profit. All creativity is channelled to this end. The extent to which we are shaped by our built environment, is something not looked at enough. I’ve been in the game over 20 years and I know that is the ultimate aim. It’s a highly efficient system as well.

For how long did you work there?

I worked at Norman Foster’s on and off for nine years. Then at some point, I was considering doing a Master’s at Columbia University. Since I wasn’t sure if I could secure funding to do that, I just decided to travel to New York and figure it out. And I ended up working at Peter Eisenman’s firm which was really interesting because it was completely different from Norman Foster’s which is a vast operation. Peter Eisenman’s, on the other hand, is quite small, avant-garde, theoretical, and academic. But I’m really glad I got to see both sides of practice because there are certainly pros and cons to both.

It was interesting to live in New York and I enjoyed it very much, but I really missed certain aspects of my life in London. I live with my husband and my two children in London, quite close to my parents’ and sister’s houses. My studio is in the garage of my parents’ house, which is the house where I grew up. And everything happens in that house – it’s the house where Shahidul stays when he visits London. For years, all kinds of people from the art world have been coming there to have meetings with Shahidul. My mom would cook food for the guests, which they loved. I met a lot of the people that I later contacted for Shahidul’s campaign at my mom’s house.

So I was only in New York for about six months and I never did the Columbia degree.

2018 must have been a watershed year for you. In what ways, did it change your life, your way of thinking, and your approach towards your work?

I wrote an article for an English newspaper in Bangladesh called The Daily Star. And I’m just going to read the first few lines of that article:

On August 5, 2018 a message comes: “Your mama has been taken. It was soon after he did an Al-Jazeera interview…over 20 law enforcement agents, possibly Detective Branch.” My mind shatters into a million stars that try to reach you with their light.

This is also a metaphor for what happened to my life and my way of thinking. I think everything shattered and that naturally extends to my work because my work is me. I began campaigning all the time and I realised that I never want to make art or architecture without being involved in direct action. Direct action is not just limited to creating art; working with the government or human rights organisation also shapes my art.

My work is about struggle and resistance, both of which I learned about when I campaigned for Shahidul and for some other political prisoners’ release too. I learned about the terror of looking at authoritarianism straight in the eye, which is what you have to do when you fight for someone you love. And this state of terror brings you to the edges of life and death and that undeniably shapes your art and you as an artist. Because you’ve now pushed yourself to somewhere you have never gone before. In 2018, it was the fight of our lives and we had no option but to win. And I say ‘we’ because it was a collective pain.

Through this fight, I also learned about the courage you get from people from all over the world who help you – from grassroots people like students in Bangladesh to Nobel laureates and other public figures. I learnt a lot about people power. And I also learned about the intense love and support of my husband and children who stood by me and kept things together at home, as our home life completely transformed along with my transformation. I understood the need to be strategic and to balance risk, because if I had taken one wrong step, there could have been dangerous consequences. I learned the need to work with others and trust them completely as you can’t micromanage a global movement. I learned to be patient and to also ignore everyone who told me that I don’t stand a chance in hell with this.

What I really saw through the fight were the best sides of people. Activism really shows you the best sides of people and you make friends for life because you are all in it together on the edges of life and death. It’s a different way of living.

I actually can’t describe what it’s like to be around Shahidul for anyone, particularly for a child. It’s something elemental. Being with him almost takes being alive to a different level. You’re lifted to somewhere higher than the ground plane of the earth. And from that place, you dare to break and unlearn everything you thought you understood, rebuild it, and break it again.

How did you balance being emotionally close to him and the political fight that you had to do? It must have been a really traumatic time for you.

My upbringing with Shahidul had set me in good stead for this. There was a period when I was four years old living in the UK, couldn’t speak any English, and didn’t have my parents here. He was the one to look after me at that point and I clung on to him, so I have a really strong bond with my uncle. He supported my desire to become an artist from the start.

So yes, when he was abducted and tortured, it was very, very traumatic on a personal level. But then my survival instinct kicked in. We knew that by hook or crook, we were going to get him out. There’s no other alternative. I think I began to think like he did, and that was to believe that the impossible is possible and that’s why he is who he is.

Could you tell me more about the protests you did at Tate’s Turbine Hall during that time?

One big thing I learned during that time was that one act of protest leads to another and generosity breeds opportunity. For example, Shahidul’s friend, José-Carlos Mariátegui, called me up from Peru and said that he wanted to do an exhibition with this box of prints that Shahidul had left from when he did his Crossfire exhibition on extrajudicial killings in Bangladesh. So he ended up doing this protest exhibition for Shahidul in Lima, Peru and then other people around the world started doing these protest exhibitions for Shahidul. When my aunt told him about these exhibitions during one of the jail visits, he smiled, and that meant the world to us. José-Carlos then brought the prints over to London and said, ‘Why don’t you use these prints to do an exhibition in London?’

At that point, the Cuban performance and installation artist, Tania Bruguera, had just opened her commission at the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern. And José-Carlos contacted her about the exhibition and she offered to help me immediately. She suggested that we use Turbine Hall to stage a protest. This was a remarkable gesture of solidarity and generosity. She completely trusted me to do this. You have to consider here that this is an artist whose exhibition had just opened, and if something went wrong, she’d have bad press reviews and stuff. Imagine the risk she took! And this reminded me very much of Shahidul because he also takes these leaps of faith.

Activists work in quite a different way than conventional artists. They’re much less precious and less controlling in their approach to making art. And it’s because their art is not really about themselves. It’s a means to an end. It’s a means of resistance. It reminds me of a fast-flowing river, because the river is fluid and bends and turns to the current, and it picks up whoever it can along the way to reach its destination. And it must reach that destination. I think this kind of art and its beauty is also like that of a river because it’s unpredictable, wild, intangible, and it’s the opposite of a static art object or artefact.

‘Free Shahidul’ protest exhibition at Tate Modern, Turbine Hall, October 2018

You created 3D artworks for ‘Memories of Keraniganj Jail’ – part of Shahidul Alam’s retrospective at Rubin Museum NYC – and a number of drawings imagining the cell in the prison. How was the experience of listening to Shahidul’s stories and then creating them as artworks through his memory and your imagination?

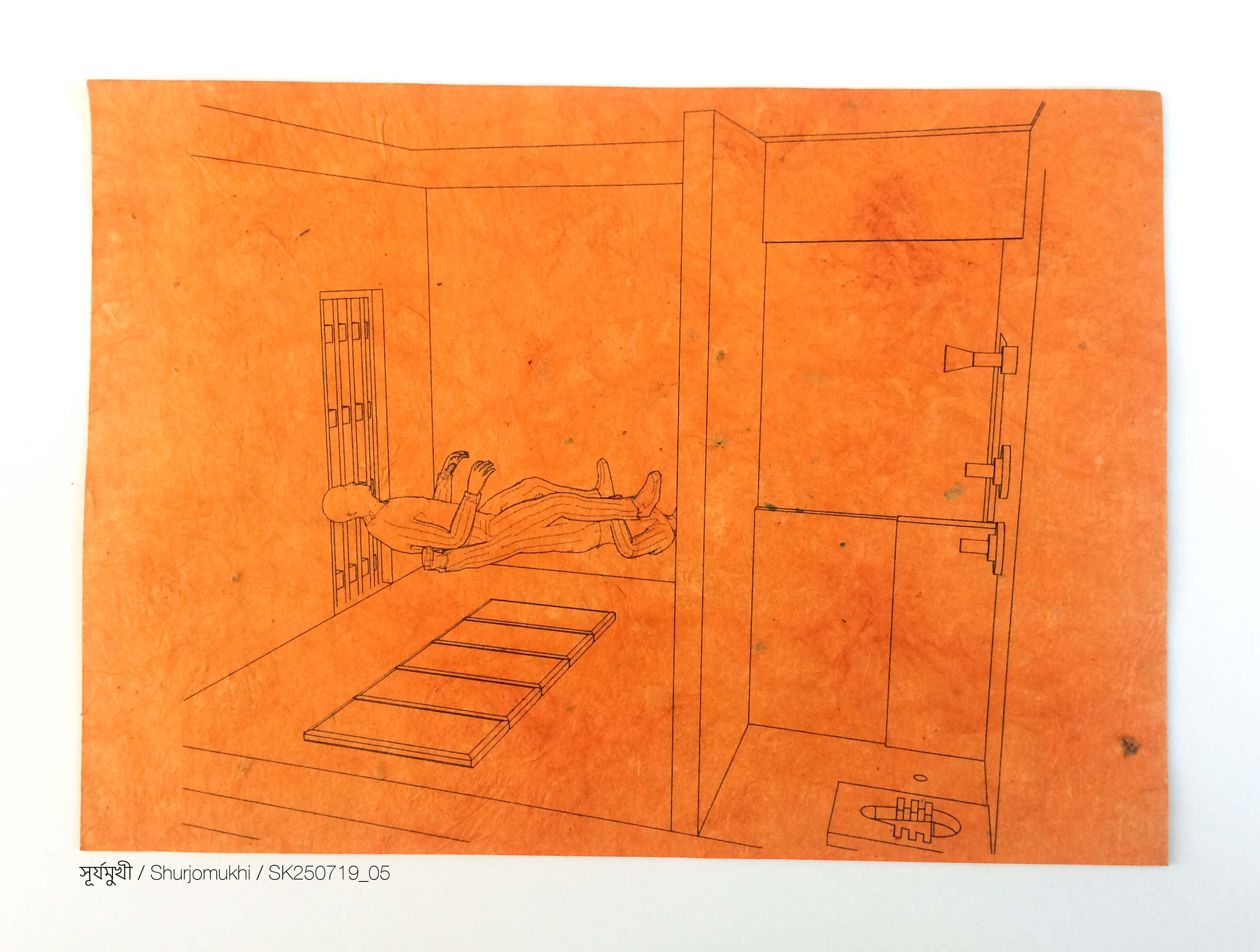

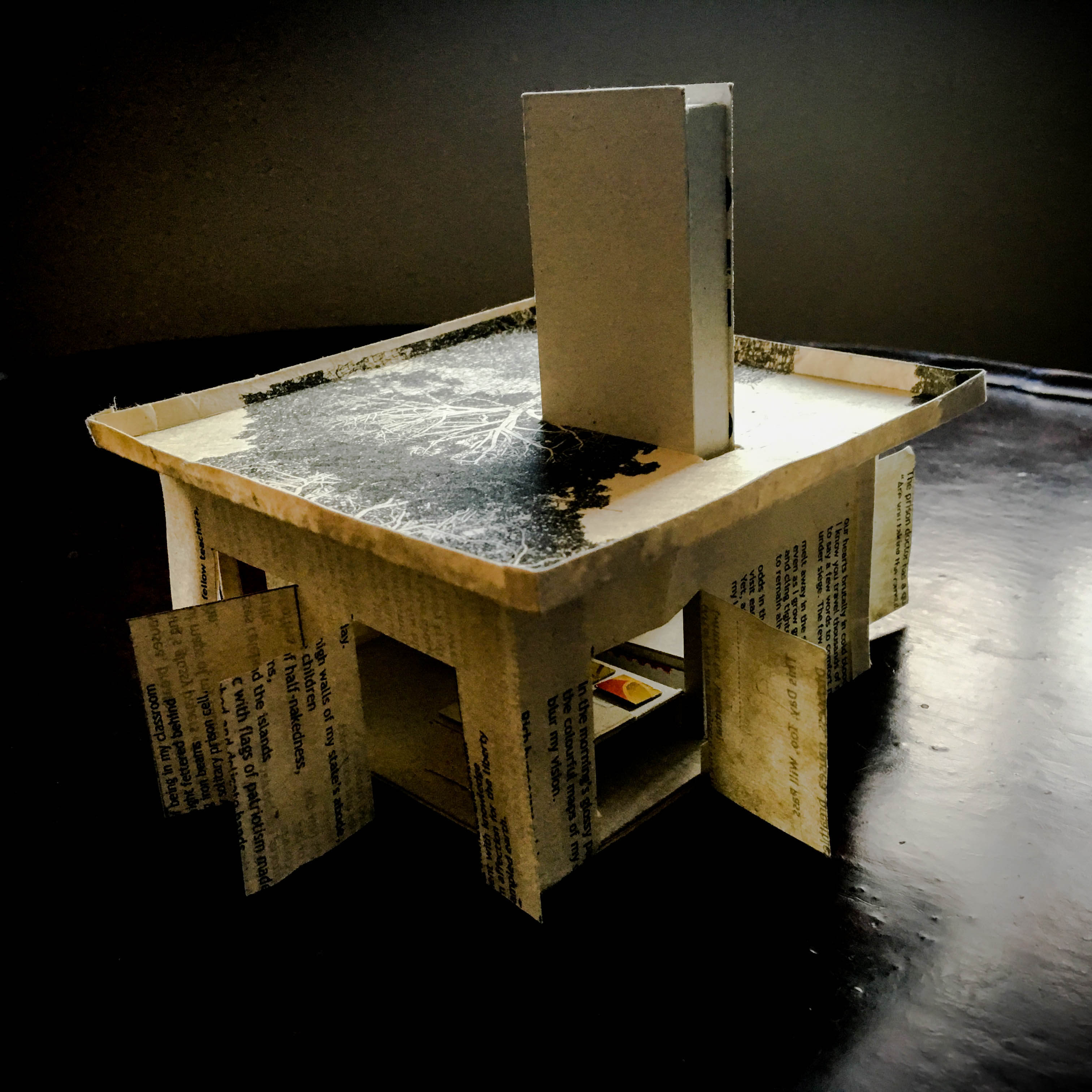

A few months after Shahidul was released from the prison, he messaged me a hand drawing he had done of an aerial view of Keraniganj jail, with the text, ‘teaching myself to draw’. I was captivated by this view of the world he had inhabited for 107 days. I had thought about that world so often in my mind, and after seeing his little aerial view, I just wanted to zoom in and get inside. That’s when the idea of making the 3D models was born.

During Shahidul’s incarceration, I imagined the spaces he occupied especially when he was on remand and experienced torture in custody. I was desperate to crawl into his cell like a worm and hold his hand so that he wasn’t alone. Since I couldn’t really do that, I used what I know – architecture. I began to construct these spaces in my mind. At first, the spaces were formless with many shades of colour. But then when my aunt was allowed to visit him once a week, she would bring us news from each visit and from these stories, the spaces in my mind started getting more detailed. After he sent me that drawing, we eventually discussed creating 3D models while sitting at Tate Modern when he visited London. We then had a few email exchanges, where he provided me with details and characters.

Through the process of listening to his stories, I was also reminded of the way he used to tell me stories as a child. Using what I had built in my imagination and his memories of jail, I began modelling the spaces and making drawings. Through the drawings, I was also progressing my own ideas on architectural theory in parallel and realising that I can never design buildings in the same way again.

I began to make many drawings and started getting interested in these dimensions in which prisoners are crammed into the cells in very specific configurations. Architecture has always taught me about harmonic proportions and golden ratios, but now I’m interested in other dimensions because my understanding of the truth has shifted. And through this, some kind of vocabulary of architecture is beginning to emerge. I don’t know what it is or where it’s going, but I just let it happen while making these models. These models are very important to me because they show the hidden world of the Keraniganj jail, this surreal netherworld of untold stories. And now that I’ve inhabited that space, the space will never ever leave me.

‘Hospital’ – Memories of Keraniganj Jail | Models made for Shahidul Alam’s Retrospective, ‘Truth to Power’, on at the Rubin Museum till Jan 2021 | Photo by Shahidul Alam

‘Case Table’ – Memories of Keraniganj Jail | Models made for Shahidul Alam’s Retrospective, ‘Truth to Power’, on at the Rubin Museum till Jan 2021 | Photo by Shahidul Alam

Koutuk Da (/কৗত3ক দা ) and his cats 1 | Keraniganj Jail Drawings

Shurjomukhi Cell 1 (Sunflower Cell) | Keraniganj Jail Drawings

In what ways specifically did the Shaheen Bagh movement move you? What, according to you, made the movement really unique?

It was the largest women’s resistance movement of our time.

I kind of grew up during the war on terror, and my whole adult life was shaped by the narratives of Muslims (and Muslim women) that were built around that war. Shaheen Bagh movement was led by a lot of Muslim women, among others. It not only challenged patriarchy, but also stereotypes of Muslim women. And this includes certain strands of Western feminism in which they present us as comparatively backward or repressed or invisible, or unable to act without the agency of men. Shaheen Bagh protests challenged all that. These women were way ahead. I haven’t seen a movement like that in the western world.

The other thing that was really interesting to me about Shaheen Bagh was that it was a collective struggle that spanned across classes. They were fighting for each other – they were fighting for their fathers, their husbands, their lovers, their sons – and they were really fighting with everything they had. These weren’t traditional activists. These were everyday women who had come out of their homes to defend their country against the forces of fascism, against citizenship laws, and to fight for a secular constitution.

And it’s not only the fact that they resisted, but it’s also how they resisted that warrants attention. Because at Shaheen Bagh, these women managed to create a safe zone amidst the state violence and brutality. This was especially interesting for me as an architect. In the space they created, there were libraries, educational facilities, and places for children to draw incredible works of art.

When did you start thinking about starting Turbine Bagh?

My area of interest has mainly been Bangladesh, but the politics of Bangladesh is inextricably linked to India. So I’ve been following the CAA protests since December 2019. I had connected with a few activists based in the UK and we were thinking about what we can do to raise awareness because there was hardly any. While we were pursuing a lot of political channels, we realised we’re not going to get very far with just that. And so after the Shahidul and Tania Bruguera protests I had done in Turbine Hall, it was quite a natural move for me to think about organising a protest about CAA in the Turbine Hall. I proposed the idea to the other activists and they liked it. And that’s really how it started.

The protest was due to be staged on 28 March, 2020. But a few days prior, the museum had to shut down because of Covid-19. So I kept the Instagram platform going and the work continued to come. Many artists from India also began to contribute to other causes through the platform. One example of this is the ‘Free Kajol’ campaign. Kajol (Shafiqul Islam Kajol) is a photojournalist who had disappeared and is now jailed in Bangladesh. And my daughter actually made a samosa packet about this and Kajol’s son happened to see it and got in touch with us. Some of the artists even made art for the Black Lives Matter movement.

The amount of work that artists keep sending me has been constantly increasing, and I think that’s a testimony to the urgency of the situation. And we are now at a precipice. This ‘Hindutva’ project has been unfolding for many years, but it’s now being implemented at a breakneck speed and in a highly systematic way. So I’m going to just leave Turbine Bagh to evolve as a resistance movement as it needs to. For instance, recently, some activists in the UK got in touch with me to sign a letter to the UN about the Hathras rape that happened in India and about violence against Dalit women. I was proud to sign that letter on behalf of Turbine Bagh.

I want to talk about the Samosa Packet movement – how did it start and evolve?

In February 2018, this is way before Shahidul went to jail, I bought a packet of samosa (called Singara in Bangla) outside Drik. The packet really intrigued me because it was made from waste printouts of court lists that were state’s cases against citizens. And as you know, both in Bangladesh and India, there are thousands of these cases. And both Bangladesh and India also have thousands of these packets which are very familiar to people in these countries. These packets are made from recycled waste paper, and some of the packets I found had nationalist poems on them and some had propaganda news clippings. I got obsessed with these packets and started collecting them. For me, they painted a portrait of what was happening in the country in a way.

Then when Shahidul was jailed by the government, I wondered whether his court case would ever appear on a samosa packet, and somehow that thought made me start making my own packets with my version of the news. So in a way, it was to combat propaganda. I wanted to give these packets to street vendors so they also become a part of the ‘Free Shahidul’ campaign. That was how the idea of the Samosa Packet movement was born. It was interesting for me because this object reaches and delivers news to all kinds of people beyond the art audience.

When I started Turbine Bagh, I was reading an article about food at the Shaheen Bagh protests. It was basically saying how there’s great food at the protest, and even some of the police officers were eating the food. And the common greeting was ‘Have you eaten?’. So something connected with me and I thought the protest art should be on samosa packets which can be shared at various protest sites. It was a way of using this very familiar object in South Asia in a different way. It was also very practical and cost-effective. Various artists started emailing me their work, and then I would combine that with things that came to my mind in response, which could be words or newspaper clippings, and sometimes words from speeches in London. And I was printing these on just really old papers I found in my mom’s cupboard using her cheap, crappy printer, and then just photographing them and sharing on social media. My whole family became a part of this!

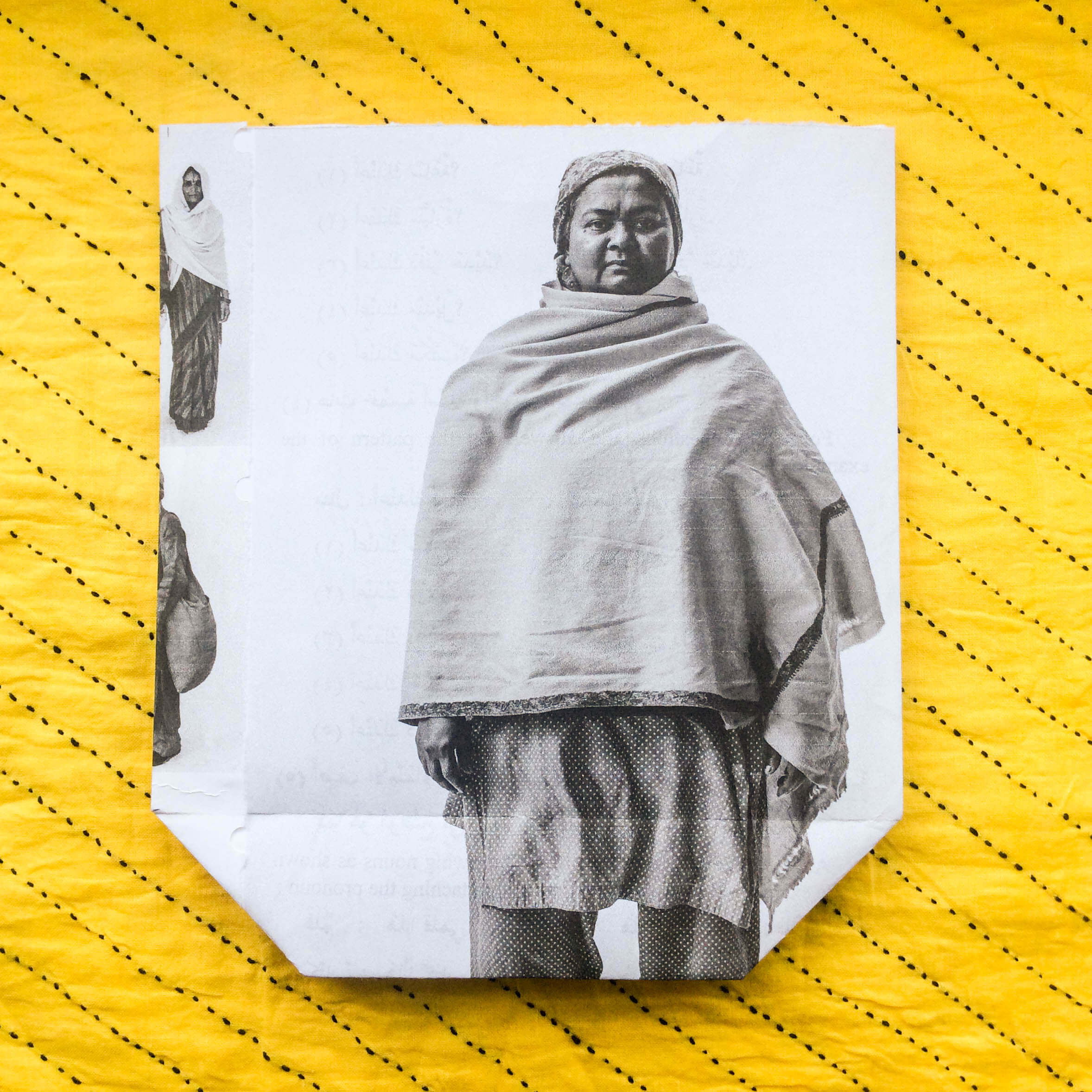

Samosa packet (িস.ারা /ঠা.া) by Sofia Karim featuring photographs by photojournalist, Harsha Vadlamani ▪ The images are from his series ‘Chalo Dilli’. Harsha emailed Sofia his work and said: “My series ‘Chalo Dilli’ is an exploration of the culture of dissent and protest in India. Since 2016, I have been interviewing and photographing Indians who come from across the country to protest at Jantar Mantar.” ▪ Mehrunnisa, the woman whose image fills one side of the packet, was one of the dadis at Shaheen Bagh.

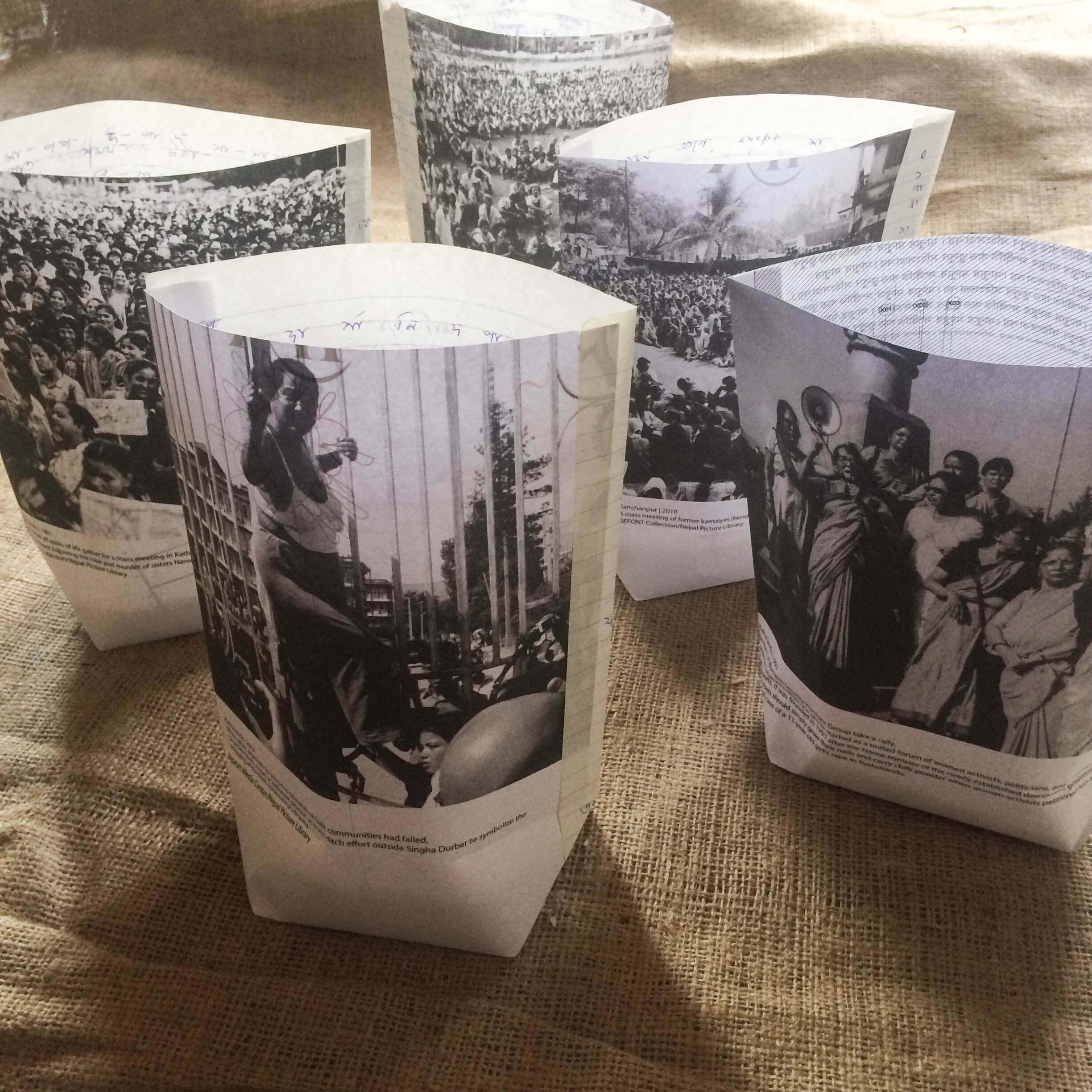

Samosa packets (িস.ারা /ঠা.া) by Sofia Karim featuring photographs from Nepal Picture Library. The photos show vibrant resistance movements addressing issues including rape, caste, misogyny, and bonded labour.

The fact that authoritarianism tries to suppress or control art is testimony to art’s ability to speak the truth about power and challenge power. If it didn’t have the ability to change things, it would not be seen as a threat.

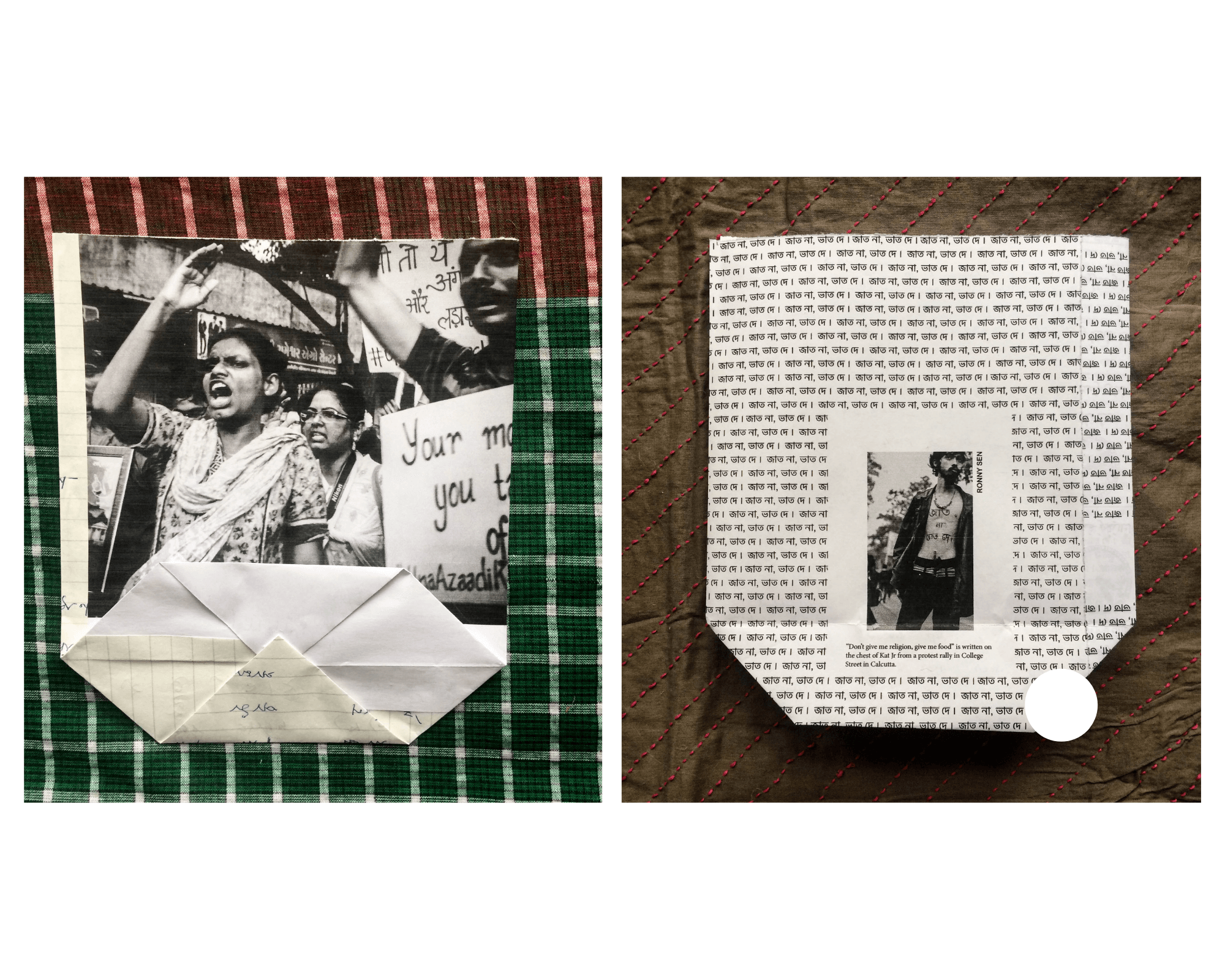

Left: Samosa packet (িস.ারা /ঠা.া) by Sofia Karim featuring photographs by Shuchi Kapoor▪ The photographs are of the Dalit protest in Una in 2016 | Right: Samosa packet (িস.ারা /ঠা.া) by Sofia Karim featuring photograph by Ronny Sen: “don’t give me religion, give me food” is written on chest of Kat Jr from a protest rally in College Street in Calcutta.

What’s the role of an artist in today’s world – I know it’s a very broad question, but perhaps we could look at it from the context of India where human rights violations and fascism are probably at an all-time high right now. How can artists really play a real role in all of this? Do you feel that artists need to have an inherent responsibility towards this?

The fact that authoritarianism tries to suppress or control art is testimony to art’s ability to speak the truth about power and challenge power. If it didn’t have the ability to change things, it would not be seen as a threat. Why are India and Bangladesh both jailing artists, poets, singers, and writers? These are the people who have dared to voice the concerns of the oppressed. The art of dissent has always been there and it’s played an extremely crucial role in resistance movements. It’s also created some of the greatest works of art.

Do artists have a duty to make this art? I think most artists I know who make this kind of work feel compelled to do it. They might also like to paint butterflies and trees as they’re interested in getting close to the pulse of life and human experience, and the wonder of a butterfly or a tree is also part of that. And one doesn’t have to choose between one or the other. But having said that, I would be incapable of only drawing trees or butterflies or clouds again and again in the midst of such suffering.

Of course, while creating activist art is a compulsion for some, it’s also a choice because it involves risk and sacrifice. You can be punished not only by the state, but also by your friends and family for choosing a life that really tries to live with one’s eyes fully open. To be honest, I don’t even like the term ‘activist art’ because it somehow implies that this art is characterised by sacrifice, piousness, and sanctimoniousness. It gives the impression that to create this art, one must forsake beauty, mysticism, philosophy, and spiritualism. But actually, nothing could be further from the truth.

I feel that to not fight with everything that one’s got, to not use that cosmic gift that one has been granted as an artist, and to think that things will just change by themselves in this world – for me, that’s the way to forsake beauty, mysticism, poetry, and love, and to live in darkness.

And if I think that just painting butterflies is going to bring me peace and is somehow going to be an antidote to this brutality, then I’m wrong. It’s not only about the art of dissent; it’s not only about doing something for others; it’s also about looking at yourself. Do you want to be someone who shuts the curtains on what’s happening in the world outside? Then you also have to question whether you are now a part of the machinery of distraction that is designed to keep our eyes averted from the real issues in this world.

You have often spoken about ‘architecture as a language of struggle and resistance’ and also about wanting it to come closer to the human condition. Could you please tell me more about this?

Other art forms, be it literature, poetry, music, or visual art, have very much been used as a language of resistance all throughout. They all have a strong culture of protest or dissent. Architecture, by and large, has totally evaded that. It’s very aloof; it stands back and refuses to engage with the struggle on the street.

I don’t think it’s good enough to say, ‘well, we built a National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington or we have the Holocaust Museum’. Those buildings are really good and I’m not dismissing them. All I am saying is that that’s not good enough because Nina Simone didn’t just create one powerful Jazz song and said, ‘Okay I have dealt with this and I am done now’. In fact, Jazz couldn’t have the music it has if it wasn’t dealing with pain and struggle. It’s that experience that has shaped the actual form of expression. That doesn’t exist yet in architecture.

In fact, architecture has the potential to be an incredibly potent art form because it can change you, affect your body, and lead to a spiritual experience. I think if used rightly, it’s one of the most profound ways to talk about these things. And it has happened in the past. If you look at Neolithic architecture, for instance, they understood the connection with the cosmos. If you look at Islamic architecture, that’s about the expression of the underlying reality, and Western classicism is about trying to reach God. But even all that was about reaching a higher power and not about what was happening on the streets.

I spoke about how my mind shattered like stars when my uncle went to jail, and I think everything I learned in architecture, including the rules of architecture, also shattered that time. There is something about the silence of architecture that speaks to me about suffering, and I think it’s all about revealing that connection with the human struggle.

I want to talk about your project Lita’s House where you also collaborated with a poet and a music composer – how did it come about? What inspired the project and the idea of ‘Architecture of Disappearance’?

As I said, I’m always involved in direct action in my work. As I was coming across these cases of poets, intellectuals who’d been jailed, I began to be connected with their families and hear their stories as well in some of those cases. At the same time, I was having conversations about all this with my friend who’s a poet (Rachel Spence) and whose partner is a musician (Michael Rosas Cobian). I’ve had many conversations about this idea of silence in music with Michael as silence and the structure of silence is really important in his music. During these conversations, I felt an urge to create this house.

Lita’s House is an imaginary house for those who’ve disappeared in India and Bangladesh, those whose cases I was working on. It’s a mirror world of authoritarianism and fascism. Although I didn’t set out to subvert levels of architecture or anything in this project, it was interesting for me to create architecture in this way. It didn’t matter whether it was real or not. And, you know, some of these ideas might carry through to something I eventually build. This project was about trying to push to the edges of life and death that I spoke about earlier, and when I was making this house and its drawings, I was somehow finding myself floating towards those edges.

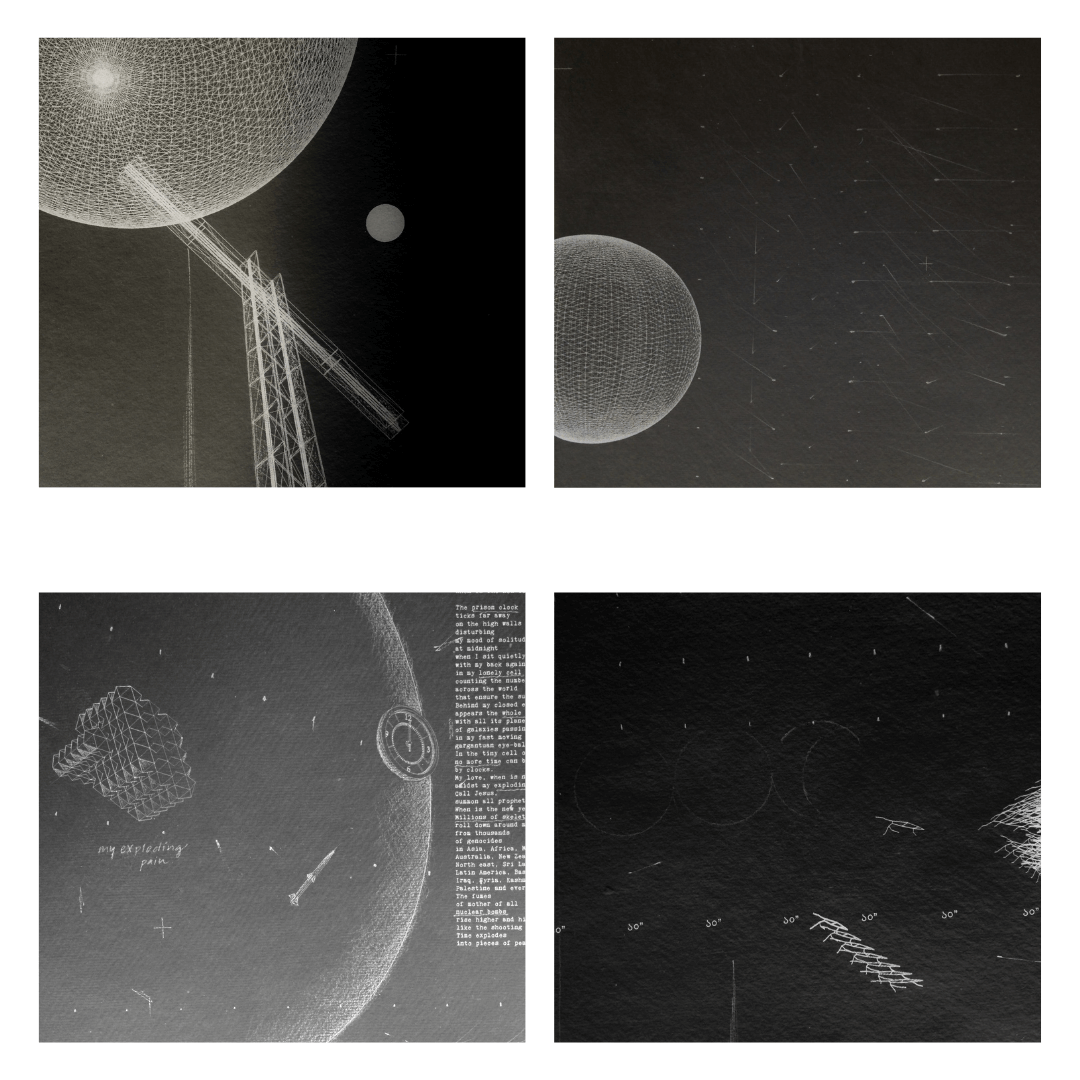

Top left: Lita’s House – The Gallows – Shahidul talked about walking past the gallows in Keraniganj jail. “The tide will turn,” he says | Top right: Lita’s House – The view from Lita’s window | Bottom left: Lita’s House – When is the New Year? (Based on the poems of Professor G.N. Saibaba) | Bottom right: Lita’s House – Great Bear I (Keraniganj Jail, Kechki file)

When did you start seeing writing as a medium of expressing your thoughts, opinion and ideas? Does it have a relationship with your visual art and architecture?

Writing for me is a part of my way of thinking and a way to sharpen my thought process. Often when I’m working on a drawing or a piece of art or architecture, I’ll stop and start writing about it. And I find that when I eventually go back to making the work, it’s a sort of interesting, tangible relationship.

I think part of it is because of this thing we spoke about – should artists make art for the sake of art or should it have a role to play. I think when I look at a piece of artwork, I always think about what the artist is trying to say. Therefore, I try to say something with every piece of work I create and writing helps me with that. It unlocks things I didn’t even know I wanted to say.

One of the key aims of your work is to spread awareness in the West about the crucial issues facing Bangladesh and India right now – what have you been seeing in terms of that involvement in current times?

It’s really bad. In terms of both India and Bangladesh, a lot of why these leaders can get away with things is because they have no real challenge. The West chooses the nations it wants to demonise. If you generally take names of countries like Iran, Turkey, Russia, China to people on the street, they will think of oppression, religious fundamentalism, etc. But if you mention India, chances are that they won’t think anything like that. The lack of awareness, certainly in the UK, of what’s happening in India is alarming.

I think there are various reasons for that. The governments in the West are quite happy to endorse India right now and to me, that says that they don’t have a problem with Hindu fundamentalism. And they don’t in many ways. They have the common “enemy”, which is Islam, and they don’t feel threatened by Hindu fundamentalism in the way that they feel threatened by Islam. Secondly, people still have very exotic notions about India and they still associate India with yoga, meditation etc. In their mind, that’s the superior way to live, which obviously fits quite comfortably with Hindutva, which wants to be seen as the superior way to live. These exotic notions are extremely hard to break through.

Made of Sofia’s mom’s old microbiology notes and Professor Paul Brass’s texts. “Renowned Political Scientist Paul Brass’s book Forms of Collective Violence: Riots, Pogroms, and Genocide in Modern India is presented as evidence by the Delhi Police in its chargesheet filed against JNU Ph.D. scholar Sharjeel Imam, who faces charges under draconian UAPA… The Delhi Police, which has filed a 600-page chargesheet, against Imam said that JNU student became “highly radicalized and religious bigoted” by reading “only such literature and not researching alternative sources.”” Maktoob Media article 21.09.20 @maktoobmedia

Maquette for 25M2 house. Designed in the time it took to listen to Bessie Smith’s album ‘Me & My Gin’. Used jailed professor G.N. Saibaba’s poems as walls.

The cover image: 'Feeding Sparrows' - Memories of Keraniganj Jail | Models made for Shahidul Alam's Retrospective, 'Shahidul Alam - Truth to Power', on at the Rubin Museum till Jan 2021 | Photo by Shahidul Alam