I don’t think art can save the world in ways that are as immediate as, say a vaccine or plastic-eating bacteria. But I do believe that art can change people in ways even they can’t articulate, and people in turn do save the world. Whether or not your studio practice is political, making art always is and in that sense, like a canary in the coal mine, it can reveal how tolerant a society really is, which is useful in our current climate.

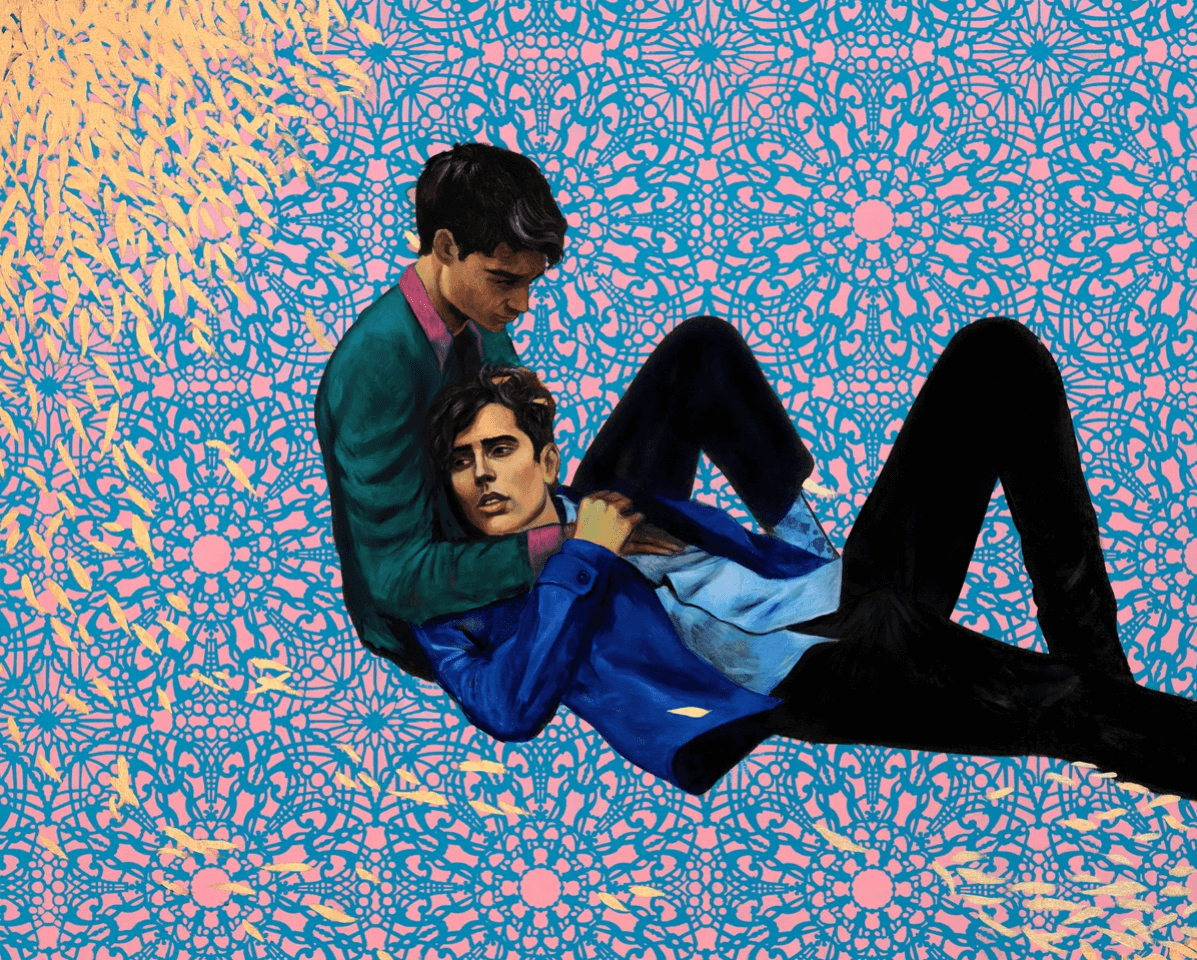

Komail Aijazuddin is a visual artist and writer who lives and works in New York City and Lahore. His art journey started as an investigation into figurative Islamic art and has since evolved to include a larger vocabulary of religious art – illuminations, altar pieces, paintings, scrolls, votive objects – as access points to queer contemporary identity.

His academic credits include BA degrees in Art and Art History from New York University, NY (2006) and an MFA from the Pratt Institute, NY (2010).

Edited excerpts from our in-depth conversation with Komail:

You were born in the UAE and then moved to Lahore, Pakistan. What are some of your memories from that early time?

I was about five when we moved to Lahore and my memories of that time are fairly vivid, so I suppose it depends on which genre of my trauma you want to go into (laughs). In the years immediately following the end of General Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship – late 80s early 90s – there was a wave of people returning from the Gulf states to Pakistan with this sense of renewed hope in terms of Pakistan and its democracy.

I was initially put into an American school – lots of show & tell and chocolate milk. But shortly after, I was enrolled at a local all-boys school in Lahore, an altogether less glamorous experience where I spent the next 13 years avoiding having to play cricket.

What were some of your creative influences at that time?

Honestly? Disney cartoons and Oprah. I was always drawn to drawing and campy animation – Mary Poppin’s corset, Cinderella’s glass slippers, the Little Mermaid’s shell bra, etc. Cartoon Network was new in Pakistan and so there was this explosion of western visuals and storytelling through drawing. Looking back, I was also influenced by the period architecture and ornamentation I saw around me in Lahore. But the truth is, like any child, I usually responded to the things I found around the house. Some of those early themes influence my studio practice to this day.

Please tell me more about Aitchison College. What were those years like?

Traumatic. I was a very effeminate child which is not an easy or inconspicuous thing to be in an all-boys school obsessed with sports. The campus was beautiful but the ethos of the school was a confusing mix of vestigial colonialist fiction and internalized self-hatred, all wrapped up in the gauze of white supremacy. For my time there, it was a stuffy, authoritarian prison that punished my interests like reading, writing, or painting. The art room was the sole refuge for people like me, a safe space where we were able to exist in relative peace. The heaviness of that sense of displacement – where you feel like the whole of you is wrong because everyone keeps telling you it is – takes years to undo, and I’ve spent a lot of my career examining those early fissures, which is why I suppose a lot of my writing has to do with that period of my life.

How did you arrive at the decision to study art professionally and then go to an art school in New York?

After my first visit to New York at age 12, I just knew on a cellular level that one day I would live here. I had very little precedent in terms of what a working artist’s life looked like. I had met a few artists growing up, but it still felt like a very stratified, opaque world with no easy access point. Despite everyone telling me artists make no money and I should be a doctor instead, I knew was that I enjoyed writing, painting and public speaking in a way I never enjoyed organic chemistry.

After school, I attended McGill University in Montreal for a year but eventually transferred to NYU because of its Art History. And while living in New York was everything I’d hoped it to be, I slowly became aware of the institutional ways in which America as a whole was changing in those early years after 9/11.

Can you tell me more about your experiences at that time?

I was raised on American TV and movies, and therefore, grew up believing that the ideal of the ‘American Dream’ was real – that America was a safe, kind and fundamentally welcoming country. The version of the States I encountered when I arrived was very different, both as a person from a Muslim country and as a gay man. The early paradox was that my Pakistani-ness was seen as antithetical to my queerness, which was instructive since it was the first time I recognised the power of the foreign gaze. The institutional hostility against young Muslims males in those years – the body searches, the hours of interrogations, the presumption of violence – forced me to confront the inventory of my own beliefs and sense of identity, of which Islam had never been a major part. ‘Well,’ I thought, ‘if religion is something that I have to talk about here every single day, then what exactly are my ideas about it? How do I synthesize those into a coherent argument? What is my argument? What is personal faith?’

There’s a sense of mysticism that is baked into the subcontinent that it’s far older than the organized religions. The great thing about that is that you grew up with a deep sense of non-denominational spirituality. The flip side is that often no one really goes in depth about what exactly people believe in. I became very interested in the intersection of personal faith and public morality – of nationalism and religion being used to define a country, which is something that Pakistan had been negotiating for a long time and India has been confronting in the last 20 years. How do you brand a country? What are the consequences of that branding? Who gets to be part of that brand? Who doesn’t? What happens to them? One of the interesting things for me about cities like Venice and Marrakesh (my two favourite cities outside of New York) was that these places have enormous Western as well as Islamic influences. There is a pervasive sense of meeting and combining in a way that is symbolic of something larger, and I was interested in exploring that idea. I suppose I was trying to find out where I fit in.

When I first arrived in the US in 2003-2004, it was an ambivalent time in America, particularly in New York, not just for being a Muslim but also for being gay. New York was a lot more multicultural and you don’t necessarily always feel like you’re in the rest of America when you’re here but it was also extremely indicative of a general shift in tone in the US. After college, I went into human rights before eventually pursuing a graduate degree in painting. I suppose it was an effort to reconcile with what I had imagined I would find here and what it really was.

The art room was the sole refuge for people like me, a safe space where we were able to exist in relative peace. The heaviness of that sense of displacement – where you feel like the whole of you is wrong because everyone keeps telling you it is – takes years to undo, and I’ve spent a lot of my career examining those early fissures, which is why I suppose a lot of my writing has to do with that period of my life.

So the direction you took in your work happened quite organically because of the experiences you had.

Yes. I mean, I’d always been interested in figurative art and how to draw the human body. Most history of art tends to be the history of religious art simply because that’s the kind of art that was important enough to be preserved through human history until quite recently. I felt an initial excitement when I saw art historical paintings using stories familiar to me through the Quran. It was not uncommon to see Italian, Spanish or Dutch paintings depicting versions of stories that I had been told in Islamic studies classes in Lahore. The idea of Mary or the Annunciation, for instance, which is a very common subject for votive paintings, was an immediate access point. I was essentially looking for all the links I could find that grounded me in the western canon, and used Art History to access them.

Coming from a post-colonial society, I also insisted on a sense of ownership on Western traditions in how, for example, I could claim Jane Eyre as much a part of my artistic lineage as Manto without collapsing in on myself. Those invisible acts of conjoining helped me navigate an America where a lot of rhetoric at the time was whether you are with us or against us. So it was interesting for me to visually be able to explore that division.

What were the themes in your earliest work?

A lot of that had to do with coded representations of queerness but also with the generalized anxiety of non-belonging. I’d grown up being bullied at school for being Shia, so the idea that I was now meant to defend being a Muslim to a white world that saw my bullies and I as the same person felt confusing. I started Shia stories as a narrative structure for my paintings, as a way for me to explore what Islamic art – or rather art from a Muslim country – looked like for me.

A lot of the early work was created once I moved back to Lahore after grad school and revolved around the idea of the sacred and profane. Blasphemy charges were beginning to be weaponized all around South Asia at the time, and I wanted to know what made something offensive. This led to my first series of altar pieces, constructed with scenes inside that could be hidden behind appropriate covers should your house be raided by the religiously myopic. There was a precedent in Dutch painting on wood in which the pieces would have nudity that could be hidden behind mini doors and I liked the sense of danger and control that idea inferred. I think it’s interesting to interrogate the ways in which religious beliefs become public policy and how tolerance for them can evolve in cultures where religious affiliations are often akin to public performances.

I want to understand the significance of the title ‘Icon’ that you use in a lot of your work.

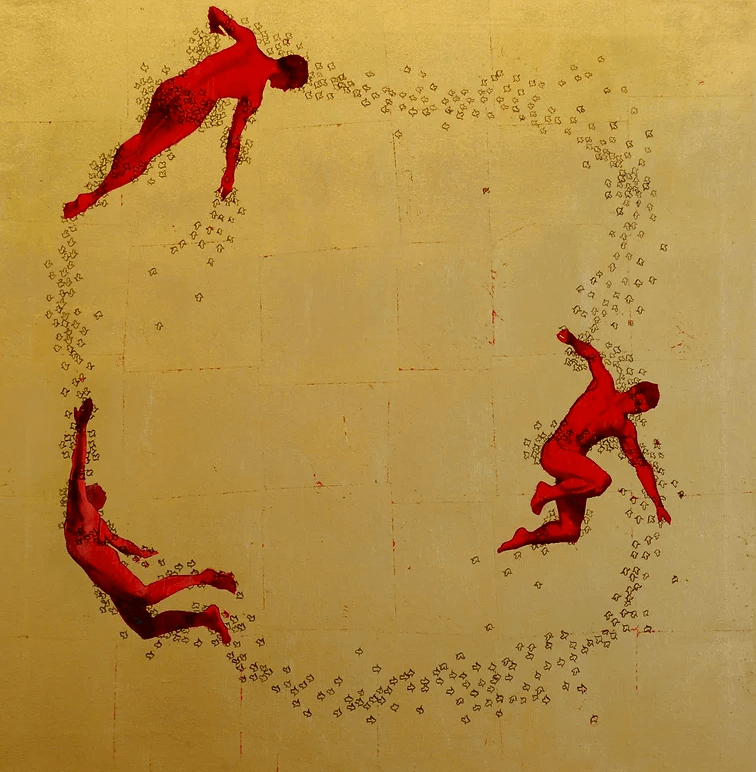

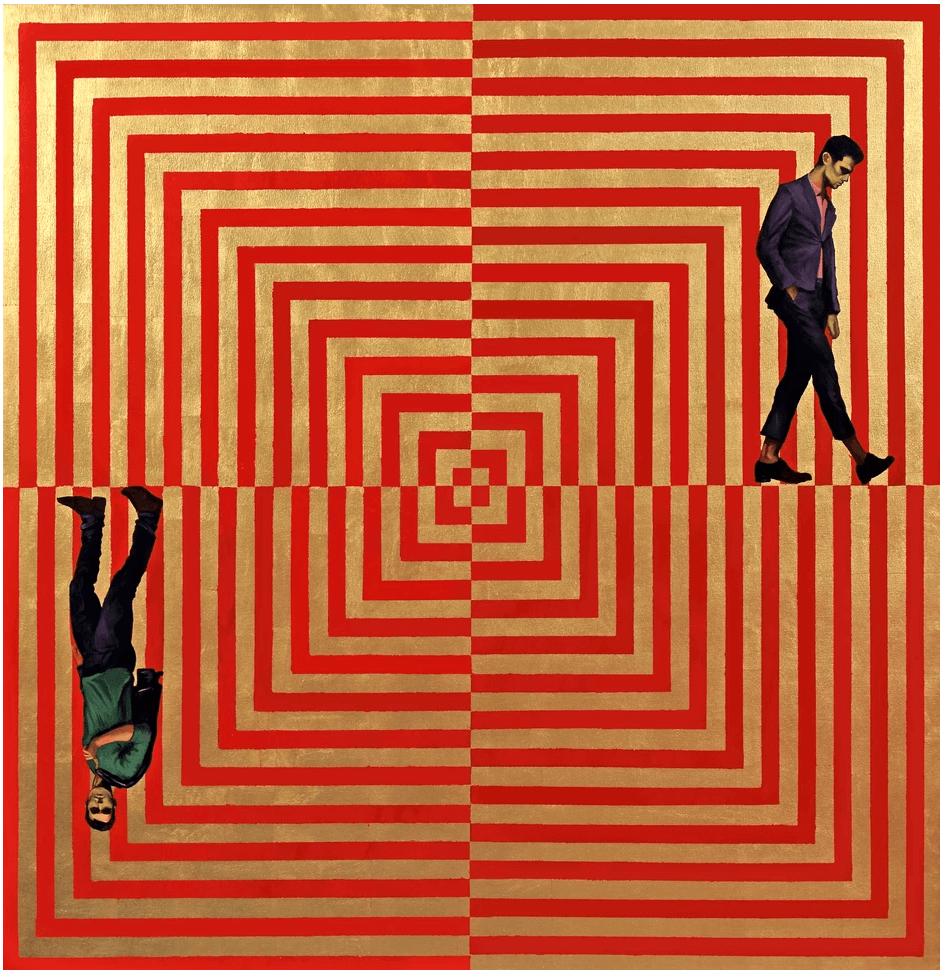

An ‘Icon’ refers to any religious portrait really, but in my work, I center Byzantine-era portraits which often used gold leaf backgrounds to indicate divinity. I extended that idea so that in my work any single portrait against a gold leaf could be recognized as an object of veneration, and by extension, any person too. As far back as NYU, I was painting a series of portraits of Muslims I knew, all against gold leaf backgrounds to show the divinity in the everyday.

Gold leaf was a very interesting medium for me, both from a capitalist point of view – because it literally puts value onto a canvas – and also as a formal element of mark making. The high reflective quality means that the gold leaf is intensely aware of the space it inhabits, and is able to change color and hue depending on what or who is around it. In that sense, many of those old Byzantine portraits are as interactive as some contemporary installations. It was also interesting to play with the idea that how in a world where we consume most art on a screen, something like gold leaf isn’t necessarily experienced fully until you’re right in front of it and are able to see your reflection staring back at you.

![]()

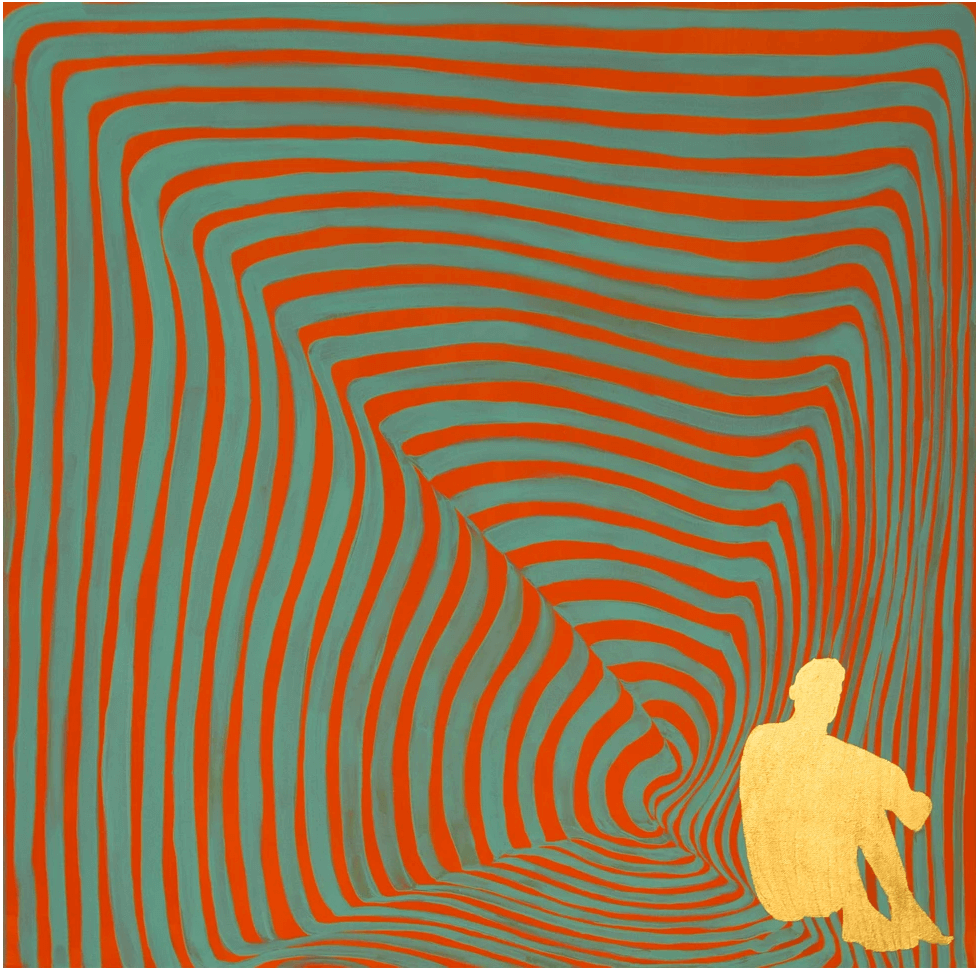

Pakistani art is generally uncomfortable with the body. There is an unsaid but clear parameter of what you’re allowed to talk about and what you’re allowed to be interested in when exhibiting there, particularly when it comes to political realities.

How do you receive reactions/conversations around your work? Does that inspire you in any way?

I’ve found that the reactions depend on the audience and the kind of work I’m prepared to display. When I was showing the ‘Icons’ in Grad school, a lot of the people weren’t necessarily a fan because it was rooted in a very old kind of traditionalist painting which they found uninteresting, but it also sparked debates simply because the subject matter was consciously non-white. When I showed in London, the Brits had a very different reaction that invariably led to them talking about the Raj, while viewers in Pakistan got more of the religious references but often studiously ignored any connections to queerness or sex.

Some reactions were surreal. Once a man bought one of my larger paintings, and somehow, he later became convinced that it was possessed and eventually had an actual exorcism performed on the piece. Regardless of my own opinion on the matter, the exorcism was a testament to the power (real or imagined) of images and that is probably why they are still objects of worship and communication thousands of years on.

When you are exhibiting in Pakistan versus exhibiting in the US, does self censorship come in and in what ways? How does it influence what you want to showcase?

Pakistani art is generally uncomfortable with the body. There is an unsaid but clear parameter of what you’re allowed to talk about and what you’re allowed to be interested in when exhibiting there, particularly when it comes to political realities. Often that kind of constriction allows for some truly inspired pieces, but I think it can get cancerous over time. Many Pakistani artists use the Persian miniature tradition to make great work, but what surprised me when I first moved back to Lahore was that I didn’t see many doing figurative sculpture or large scale installation art. It was as if there was a line that demarcated what was appropriately Muslim, visually speaking, and then there was everything else.

Nudity was probably one of the obvious things that I would self censor when working in Pakistan. I have created several bodies of work that I’ve never exhibited there at all. I think it comes down to a sense of safety and to arriving at a place in your life where you become comfortable enough to talk about yourself.

As an artist, you eventually have to get over your own self-censorship to make work that is true and honest. But to do that, you have to confront the corrosive shame that masquerades as a sense of modesty and honor in South Asian culture, which is not easy or painless.

How do you see the role of art in today’s world – considering everything that’s happening around us?

I don’t think art can save the world in ways that are as immediate as, say a vaccine or plastic-eating bacteria. But I do believe that art can change people in ways even they can’t articulate, and people in turn do save the world. Whether or not your studio practice is political, making art always is and in that sense, like a canary in the coal mine, it can reveal how tolerant a society really is, which is useful in our current climate.

One way this has manifested for me is whenever I come across the depictions of blood in the works of Pakistani artists, including my own, we rarely acknowledged whose blood it is or who spilled it or how. Devoid of these details, which the artist cannot include in the work for fear of retribution, the art becomes an abstract way of talking about any number of political realities while avoiding getting caught in the crossfire of offending the very people we are afraid of. But plausible deniability isn’t a sustainable critique in the long term and eventually collapses under the crushing weight of censorship.

It’s interesting to look at art as a barometer for a culture’s interests. For example, there are queer filmmakers working in Pakistan, producing fantastic cinema and sharing it abroad, which may be surprising to anyone who thinks Pakistani only talk about religion. Conversely, I think mainstream Bollywood (which was always lightyears more modern in its sense of self) has become a lot more right wing in the last 20 years which I guess is a reflection of India itself. But while you can understand trends through art, I’m not exactly sure whether there is an answer to your question. I do know that my answer to our world’s problems was to leave art for a little bit and go into writing.

Arriving in the US as an immigrant for the first time during the Trump era was weird. Despite the chaos, I felt a sense of relief because much of the discord that I had sensed in the early 2000’s as a student was now bubbling to the surface of the country’s culture and other people could see it.

Let’s talk about your writing then!

Let’s! I spent the last five years working on my first book – a funny memoir called Hope and Cake about musicals, queerness, and self-acceptance, and I’m thrilled to say that the manuscript was recently sold to Abrams Press in New York and will be published in the Fall of 2024.

Humour is a big part of my writing practice. Laughter can immediately disarm and connect two otherwise separate individuals, and is a great way at getting tremendously complicated ideas across to people without them necessarily feeling being preached to. Humor puts you and the reader together versus the problem, rather than it just being you versus the reader.

I know right now you’re on a break from painting, but was there any point where your writing kind of informed your painting or vice versa?

I consider them different mediums, much like watercolors or oil paint, that I can move between depending on which medium is the best for the idea I want to express. For a long time my writing persona, who was funny and camp and obsessed with pop culture, was decidedly separate from the painter in me, who was rather more sulky and spent a lot of time thinking about death in dark rooms. And while I have no issue switching between painting and writing, I think people generally find it difficult if a person does more than one profession seriously.

But I’m interested in the space where you can do multiple things well and how that translates in your work, which is probably why I’m quite obsessed with Broadway shows, since live theater feels like a place where all of sorts of different artistic mediums – singing, writing, music, dance, acting, art, imagery – come together in a single collaborative performance.

What’s your work process like? How different is it for writing and painting?

A lot of people have asked me the value of going to art school. For me, it was the value of learning how to be an artist on a day-to-day basis. What do you do first when you enter the studio? How do you get into your work? How do you set up a studio? How to manage your time and talent? You discover these things by trial and error.

I use the mornings to exercise and get to the studio around 1 pm. I work best in the afternoon and tend to divide my work into sections. For example, the process of applying gold leaf is quite a delicate process, repetitive to the point of being meditative. You become very aware of your breath because if you breathe too fast, the gold can fly away. So in the weeks I’m gilding, I take a little more time, put on a good album, and get lost in the process of it – which is fun. Other weeks, I’m covered in oil paint and hyperventilating in a corner.

When it comes to writing, it’s essentially the same process in that I pick something to do and then do a little bit everyday until the piece takes the shape I want it to. The main difference for me personally is that I don’t listen to music when I’m writing but I do when I’m painting. It’s not very exciting, but there you have it.

How has your relationship with Lahore changed after your shift?

It is an ongoing kind of trauma. But it’s not just Lahore. As I have gotten older, the sense of what constitutes home has evolved profoundly for me. Immigrating has a way of doing that for most people.

Arriving in the US as an immigrant for the first time during the Trump era was weird. Despite the chaos, I felt a sense of relief because much of the discord that I had sensed in the early 2000’s as a student was now bubbling to the surface of the country’s culture and other people could see it.

I’ve had to consciously grow out of the idea that a lot of post-colonial cultures instil in their kids, that there is this one place and if you get there with the right credentials, everything will be magically fine. For some people, that place can be marriage, or kids, or New Jersey. So much of our life is defined by the feeling that we are one thing away from happiness but I’m interested in having slightly more nuanced conversations about things like what happens when we die or what do I consider ‘happiness’? They’re difficult questions to answer, but our responses to those kinds of questions are the things that actually shape our lives.

Lastly, what are you looking forward to this year?

Most of my summer will be spent working on the edits for the book but after I’m done, I’d love to travel. I spent most of my 2022 reading books on the adventures of South American explorers, and I’d really like to spend more time on the continent, especially because I have been holed up writing for the last three years and of course, the world was closed too. Also, this is the first time I can travel with my American passport and I’m excited to see what it’s like to go through an immigration line as a citizen. The immigration guy said ‘welcome home’ to me at JFK airport when I last flew in and I began crying which made us both widely uncomfortable but was, I think you’ll agree, a necessary catharsis.