I very much enjoy thinking, working and living independently and limitlessly. I am not the type to take orders from someone else. This may sound too arrogant but as a perfectionist, I believe I am the only one that can handle my own strict system, and therefore I prefer working alone.

As a child, the whole world was a blank canvas for Tehran-based graphic designer and visual artist, Homa Delvaray. Homa found potential in each and every surface around her – notebooks, books, walls, the ground, bodies and faces of dolls and even her sisters! Not surprisingly, when asked about her current practice, she says, “I don’t confine myself just to graphic design. If I find a medium that allows me to challenge myself better and more, I’ll use it.” Her work speaks for itself in terms of how she constantly pushes and tests her boundaries. Her ability to combine traditional Iranian culture with contemporary ideas makes her work a sharp and riveting blend of the past and present.

We speak to Homa, while she is in quarantine due to the current covid-19 situation, about her life and work. Read on:

Could you tell us about your childhood?

I was born in 1980, two years after the Iranian revolution when my country was experiencing drastic changes in its political structures that led to chaos and troubles. I was born and raised in Karaj, a major industrial city located in the west part of Tehran. Karaj was only a district of Tehran until recently and has the second-largest number of immigrants in Iran. Both of my parents had moved there from different parts of the country which had diverse cultures and languages. Hence, I grew up in a world of dualities, while living in a multi-cultural city.

I have four sisters and one brother, and we spent our childhood together during the Iran-Iraq war. Those years were tough and odd, giving us a paradoxical sensation of fear and pleasure. When I went to school, the country was suffering from a post-war economic crisis. The era was called the Reconstruction Period.

Was there anything particular during your growing up years that led you towards art and design?

As a child, I was passionate about pottery and swings. One of my hobbies was finding different ways to recreate games to entertain others. Hence, I would create plenty of new games with playing cards, board games, etc. There was no limitation for me when it came to drawing or painting – any surface around me had the potential to be a tool to express my thoughts – be it my notebooks, books, walls, the ground, dolls or even my sisters’ bodies and faces. Of course, this unrestrained behaviour sometimes caused me trouble.

When I was 9 or 10, I began to write and illustrate my own comic stories. I made at least twenty illustrated comics during my elementary school. My family was my only audience, but they were always very enthusiastic.

In the first year of secondary school, one of my teachers encouraged me to study Graphic Design in high school and that’s exactly what I did. After getting my associate degree, I continued graphic design at the faculty of Fine Arts at Tehran University.

When did you end up moving to Tehran?

While studying at Tehran University, having to constantly commute between the two cities was difficult. So, in 2011, I moved to Tehran, which allowed me to focus on my career and develop my artistic activities outside of graphic design.

As I’m currently stuck at home because of the Covid-19 quarantine, my mind has been occupied by thinking about this fatal situation. I’m constantly wondering about what the future will look like after going through this problem.

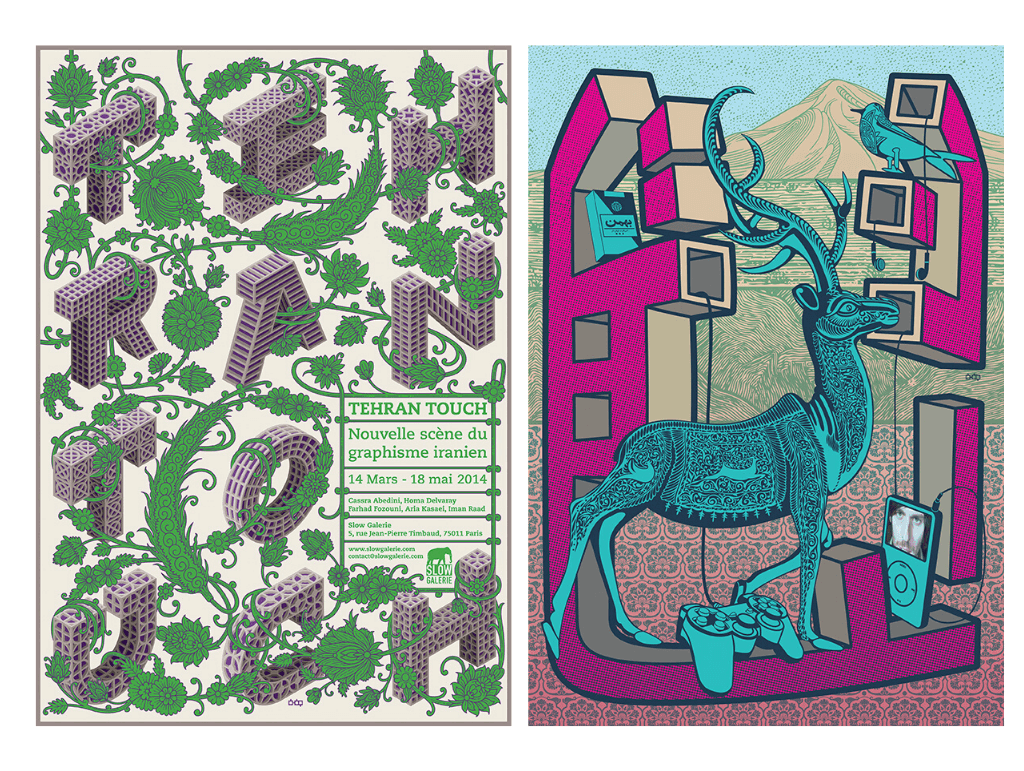

(L) Tehran Touch, Iranian Graphic Design New Scene, Slow Gallery, Paris-France, 2014; (R) Tehran; A lovely Hell!, Creatie Magazine Project, Amsterdam-The Netherlands, 2010

What aspects of Tehran inspire you and what are the things you struggle with while living there?

For me, Tehran is a symbol of fusion. Since the beginning of the 20th century, mass immigration from all over the country has had a significant impact on the city. A sense of duality began to inform the relationship between the citizens and the city due to the vast cultural diversities. Gradually, Tehran became the paradoxical, multi-polar metropolitan we know today – traditional yet modern, rich yet poor, religious yet secular – all at the same time.

I believe my art is a reflection of this duality. Even though my works have a cultural and historical background, they also communicate the contemporary world. I have always tried to amalgamate the contradiction of polarities such as west and east, past and present, local and international, and more.

Although living in Tehran comes with its own challenges like air pollution for example, I still love the city. For me, Tehran is the essence of Iran.

How did you realize you wanted to pursue design professionally? And how were your initial years of starting out into the field?

I think all the practice and research I did during my studies (2000-2005), especially those I learnt from the well-known Iranian graphic designer, Reza Abedini, have had a major impact on the path I chose.

I am from the generation that wants to be more synchronized with the constantly progressing modern technology. So we had to try techniques and methods of media production that were different from the previous generation. In our culture, there are many red lines and ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ for graphic designers, just as for many other things. According to traditional beliefs, graphic design had its predetermined principles and rules, and therefore young graphic designers like me began a new proposition by violating the fundamental framework and crossing these lines through our formalistic and extremist approach. When we started, we faced a variety of oppositions.

Over the years, the digital revolution fundamentally changed the role, function, and definition of graphic design, further impacting the attitude towards our community and diminishing the existing opposition.

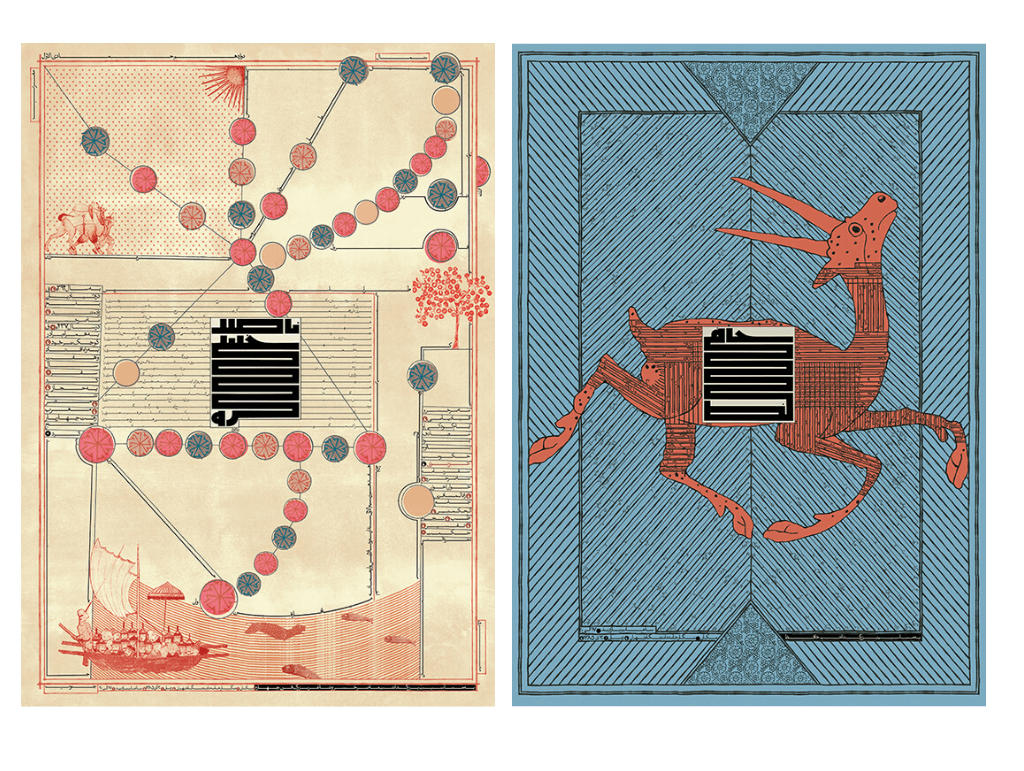

(L) Naser Khosro, from Iranian Poets Series (Thesis Project), 2006 (R) Hafiz, from Iranian Poets Series (Thesis Project), 2006

For discovering and exploring my inner world and of course achieving new ways of communication, I think that I must experience, push and test boundaries. I must be involved in all artistic endeavours and I should expose myself to a variety of art forms and ideas.

Do you enjoy working independently? Are there any disadvantages to it?

Working by yourself means making all the decisions on your own. You set your own standards and rules – the only limitation is you. I very much enjoy thinking, working and living independently and limitlessly. I am not the type to take orders from someone else. This may sound too arrogant but as a perfectionist, I believe I am the only one who can handle my own strict system, and therefore I prefer working alone.

Working independently, however, always has its pros and cons. The most challenging aspect is that you are solely responsible for any decision you make as well as in charge of providing solutions to every problem. These challenges sometimes are way too difficult and complicated to be handled by one person. Moreover, some of the bigger and permanent projects are required to be done by a team. And as I prefer working alone, I had chosen to not get involved with these kinds of projects for all these years. This path has had a lot of unknown and unexpected factors such as financial instability and lack of support from others. Thankfully though, none of them have influenced me, as I have always been very determined about my career.

Do you follow any particular creative ritual/process when you are working on a client project? And what are the things you are most particular about while executing it?

It all depends on the project. For example, when I’m supposed to design a corporate identity, the design process begins after conversations with my client and gathering all the related information. The ideation process more or less starts simultaneously and goes hand in hand with the research. Then I provide a few ideas to my clients and we agree on one, which I develop further. I divide the process into several phases and get the client’s confirmation step by step.

But when it comes to designing a poster, the process is totally different. I usually give my clients a general idea of the concept and I prefer not providing them different ideas to choose from. I also never share the design process with them until it is done. Based on my experience, they can’t really understand or imagine the final artwork I have in my mind. Fortunately, so far, all my clients have trusted me and let me do the work my way.

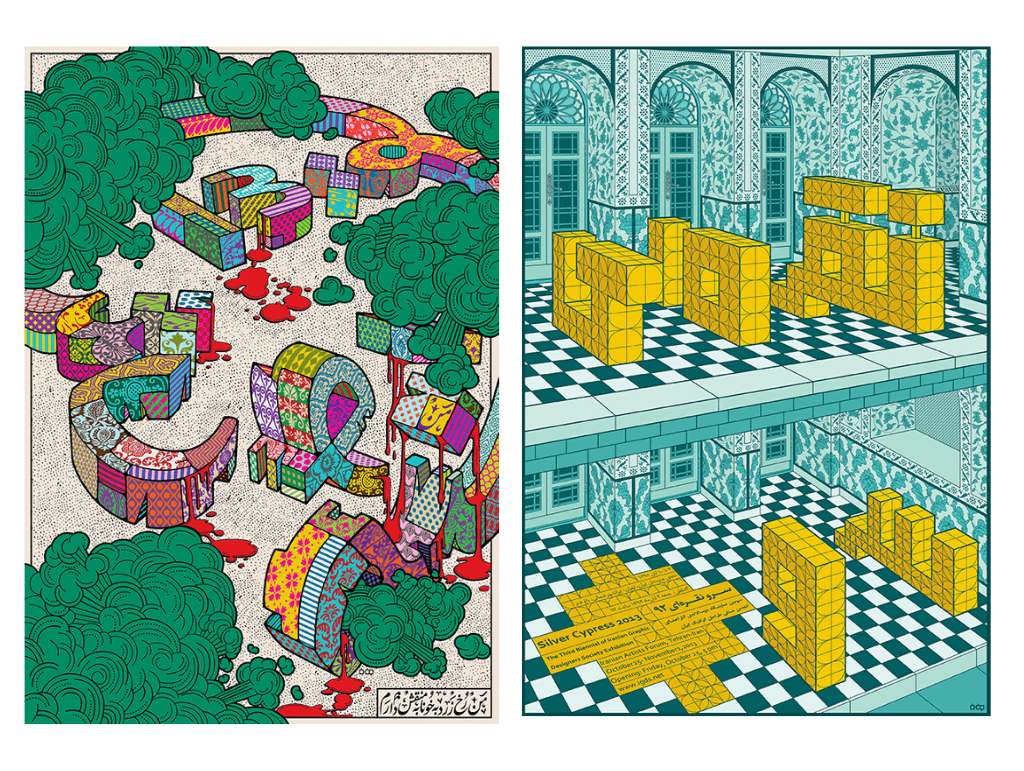

(L) ‘My Faint Face I Blush With The Blood of My Heart’, Right-To-Left Project, Berlin, 2012 ; (R) ‘Silver Cypress’, The Third biennial of the Iranian Graphic Designers Society, 2013

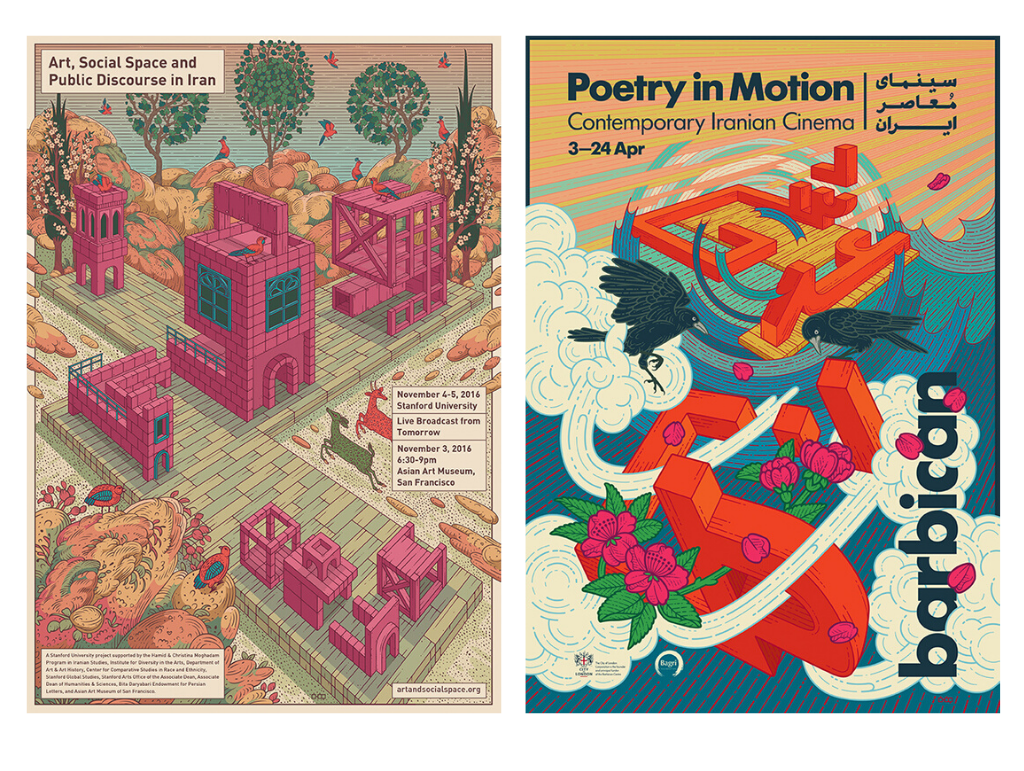

(L) ‘Art, Social Space and Public Discourse in Iran’, Stanford University Project, San Francisco, 2016; (R) ‘Poetry in Motion’, Contemporary Iranian Cinema, Bagri Foundation & Barbican Centre Project, London, 2019

Your work effortlessly combines traditional visual traditions of Tehran with contemporary ideas and motifs. Could you talk about this while giving us a behind the scene look into a project – from start to finish?

For me, the rich Iranian-Islamic historical and cultural legacy is an inexhaustible source of inspiration, both visually and conceptually. I like to rejuvenate it by incorporating these ideas in a contemporary context. I think that by shifting things beyond their borders, one can create a new perspective and give them new meanings. Besides, I believe we aren’t able to move forward if we disconnect ourselves from our past and tradition.

Most of my works are centred on typographic designs with architectural structures. I’m interested in creating carefully implemented illustrations with sophisticated details. I think by employing traditional and modern elements simultaneously, I can achieve a new and innovative visual language, which is as original and tradition-based as it is contemporary and progressive. Despite its apparent formal nature, my style does not defy concept; concept in my work is only nudged to deeper layers and placed in between intertwined forms that require decoding, as has always been the case with eastern art.

Fundamental research about the topic is the first and essential step which helps me to prepare my mind in the first place. Usually, I need a few days to gather my thoughts. After exploring the visual and textural resources in order to meet the design’s needs, my preliminary design phase begins which involves doing some sketches and developing preliminary concepts on paper until I get an idea. I usually do some sketches before working on the computer, but this can vary from concept to concept. There are times when I do the whole process via software. Overall, the design process is long, and I normally need two weeks to create my posters.

When did your interest in typography start? And tell us more about your solo exhibition at Aaran Projects called ‘Haft Peykar’?

Entering the university in 2000 coincided with the beginning of a new wave in Iranian graphic design – many events and exhibitions were being organized with typography as their main theme. Since the aesthetic and structural features of Persian letters are distinguished from Roman letters, it was considered a disadvantage by many. However, I had Reza Abedini as my instructor, and he insisted that such beliefs are due to the lack of knowledge in this field. To deal with this challenge, he gathered a number of students in his studio, including me, to study both theoretical and practical aspects of Persian Scripts for a few years. During these years, we were in search of potential and possibilities of the Persian scripts in order to apply and expand them in Persian typography. Those years had a major impact on my career, and I believe that’s exactly when my initial interest in typography was shaped. It then further developed over the years.

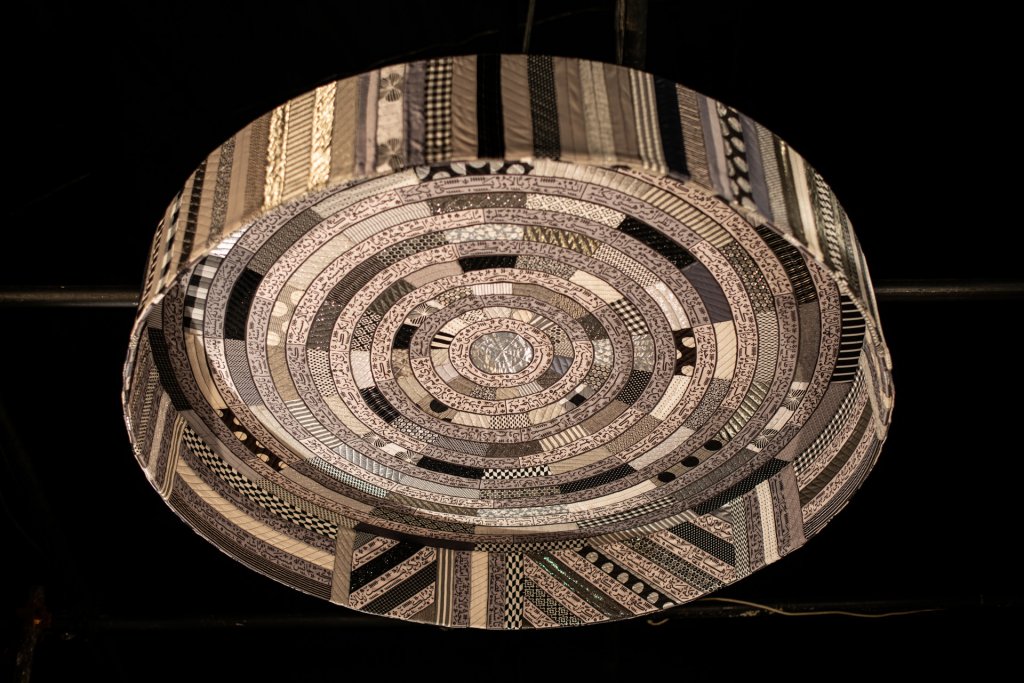

In recent years, my practice has also leaned towards fine art such as artist books and installation. In 2016, I had a fine art solo exhibition titled ‘Haft Peykar’ which was inspired by folkloric Iranian culture. The exhibition consisted of seven numbers as a textile sculpture, which was carried by wooden pulleys and was hung from the ceiling. I used the patchwork technique, hand and machine sewn, to make the sculptures. They were a combination of embroidered, colorful pieces of fabric and framed texts printed on fabric that contained traditional beliefs, religious convictions, rituals, and myths.

My concept was to use the language of numbers to narrate the do’s and don’ts, commands, rituals and protocols that the culture of Iran addresses, which in this age and time may seem odd, but residues of it have remained over centuries. Subconsciously or not, we have always carried the burden of these sediments.

What’s been the most challenging project you have worked on so far?

Without a doubt, it is ‘Haft Peykar’. It was a turning point in my career, and of course, the most experimental and challenging experience that I’ve ever had. Over the years, when I was working for the exhibition, I had to deal with many things that I had never experienced before such as new tools, materials and techniques, working with technical teams in sculpture workspaces and such. My attitude towards my life and career changed a lot based on that experience.

From ‘Haft Peykar’ Series, Digital & Silk Screen Printing on Fabric, Embroidery, Iron & Wood, Unique Edition (Private Collection), Solo Exhibition, 2018

Behind the Scenes ‘Haft Peykar’ Exhibition, Tehran-Iran, 2017

I believe the key to success in using social media is to take control of it and not let it control you. So far, I have had the ability to do that and haven’t had any serious problem with it.

Could you tell us a bit about your involvement in Dabireh Collective and Rang Magazine?

In 2006, I was one of the editorial board members of Dabireh Collective, a journal of Persian type and language, founded by Reza Abedini and a number of his former students. We all worked together both theoretically and practically on Persian typography. In 2008, I was also one of the editors-in-chief of the online Rang Magazine whose sole purpose was to expand communication between the Iranian graphic designers and design community.

“Delvaray’s visual voice possesses a poetic quality that is influenced by both traditional and contemporary Iranian poetry.” – In an article about you in Neshan magazine, writer Roshanak Keyghobadi has mentioned this. Could you tell us about this?

In the article, she compared my visual narrative to the poetic narrative of contemporary Iranian poet Mehdi Akhavan Sales. She considered both approaches as a surgical mediation. The poet employs everything from the past which is still useful, alive, active, acceptable and good to be developed and has depended on a thousand years of Persian literature. And then there is me, a graphic designer who is developing her highly ornamental and complex contemporary designs based on thousands of years of Iranian imagery.

How do you see your role as a designer in today’s world?

I think graphic design has a major role in shaping and upgrading visual culture and aesthetic perception, both nationally and worldwide. So as a graphic designer, it’s my responsibility to find out a way to achieve this. There are no pre-assigned general rules to help me achieve this goal easily, but I think it would be helpful if I challenge myself first.

For achieving an individualistic and innovative visual language, I believe that I should first work on my own visual mentality. It’s very important because visual language is capable of going beyond boundaries and languages and is one of the most powerful tools for communication. If my works are similar to each other, boring, and without creativity, no one can hear my voice. It only means that they aren’t pleasing and different enough to capture the audience’s attention.

My approach towards design is that the work should be as original as it is contemporary and progressive. In the contemporary world, many creative boundaries have dissolved, and graphic design has melted with fine art as well. I don’t confine myself just to graphic design though. If I find a medium that allows me to challenge myself better and more, I’ll use it. For discovering and exploring my inner world and of course achieving new ways of communication, I think that I must experience, push and test boundaries. I must be involved in all artistic endeavours and I should expose myself to a variety of art forms and ideas.

What’s your relationship with social media? How much does it impact your work and its showcase? Is there anything about it you don’t like?

Social media plays a huge role in communication for this generation. By taking advantage of its broader social communications, I can increase my audience both locally and internationally which helps me to further grow and expand my career. During the years of social media’s growth, I had the chance to find many of my clients via these social platforms. Keeping my website updated is one of the most challenging parts of my work, but thanks to social media, I can easily and quickly share my new artworks with my audience.

I am aware of the disadvantages of social networking as everything is controlled by it. But as it has become an inseparable part of our lives and society over the last decade, I try to avoid the negatives and have learnt to lean towards its positive impact on my career. I believe the key to success in using social media is to take control of it and not let it control you. So far, I have had the ability to do that and haven’t had any serious problem with it.

Do you have any mentors? And who are your favorite artists and designers from around the world? And favorite design resources?

Yes, as I mentioned earlier, Reza Abedini is my mentor and has been the most influential person in my career. There are many artists and designers I admire so it’s really difficult to choose, but my favorite ones would be: Milton Glaser, Istvan Orosz, Tadanori Yokoo, Henning Wagenbreth, Martin Woodtli, Richard Niessen, Robert Rauschenberg, Louise Bourgeois, David Hockney, and more.

My favorite design resources are my rich Iranian-Islamic historical and cultural legacies such as architecture, Iranian calligraphy, manuscripts, lithography, book decoration, Persian painting, carpet patterns, motifs, textures, folkloric symbols, and other traditional arts.

What’s on your mind these days?

As I’m currently stuck at home because of the Covid-19 quarantine, my mind has been occupied by thinking about this fatal situation. I’m constantly wondering about what the future will look like after going through this problem.

Are there any personal projects you are working on these days?

I’m currently thinking and working towards my new personal artistic project which is still in the early stages of its design process. But recently, I was part of an exhibition titled “WOMEN C(A)REATE”, curated by Anahita Rezaallah and Elnaz Tehrani. It was a 2019-2020 apexart’s International Open Call exhibition and presented the artists’ textile-based installations which had been made with the help of women who were in addiction recovery.

‘Neither Up Nor Down’, Homa Delvaray Installation, ‘WOMEN C(A)REATE’ exhibition, Fabric, Digital Printing on Fabric, Wood, Unique Edition, Tehran-Iran, 2020

Tags

Art, Artist, contemporary art, Graphic Design, Homa Delvaray, Interview, Iran, Tehran, Visual ArtsHoma's photographs are provided by her. ©