One of my favourite artists, Nina Simone, said this in one of her interviews – ‘An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.’ And that’s what I feel – it’s my responsibility to talk about what’s happening in the world through my point of view.

Dáreece Walker, visual artist based out of Brooklyn, New York, takes this responsibility quite seriously. Through the themes and materials of his works, that often deal with race, identity, and religion, he holds a rather large, stark mirror to what’s happening around him.

One of the things Dáreece has been consciously trying to do is create some sort of balance between talking about the harsh realities of racism and police brutality against black people in the USA on one hand and on the other, offering a glimpse into the beautiful, simple aspects of black people’s lives – his most recent project ‘Black Fathers Matter’, for example, documents black fathers simply hanging out with their children. Reimagining the past and integrating elements to create what it should have been also make his work especially powerful – ‘Our Angels’ project is a great example of that. ‘Black is the Giant’ is another brilliant project where a lot of anxiety, repressed emotions, stereotypes, and micro-aggressions related to race roll up into a colossal pile and metamorphose into a Giant to fight against all these energies.

We talk to Dáreece about the ideas and thoughts behind all of these projects over a Zoom call in the month of October in 2020. We also spoke about his creative influences, spoken word poetry, Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, and the significance of cardboard as a material in his work.

Dáreece Walker

Could you tell us a bit about your childhood?

I was born in Manhattan, Kansas, and I moved from Kansas to Colorado when I was a child. My mom’s actually from Nebraska, so I would basically go there for the summers. I used to visit my grandmother and the rest of my family there. So summertime was special since I got to catch up with everybody and not be focused on schoolwork and stuff like that.

What were some of your early creative influences?

I was a creative kid. Art classes were always my favourite. I guess that’s true for most kids because it’s not really a class. So I would always look forward to that and would try to make my projects really good.

When I was a sophomore in High School, which was in 2005, my grandparents had passed away in the same year. And I went back to Nebraska for my grandma’s funeral service. My family knew that I always keep a sketchbook. I would often draw images of posters I wanted but couldn’t afford. This was the early 2000s and it felt outrageous to spend like 10 dollars on a piece of paper to put on a wall! So I would draw posters of Michael Jordan, because I love sports, or a picture of Jay Z. I would draw them from magazines’s photos or thumbnails. So for the funeral service, my family asked me to draw praying hands with the rose for the eulogy pamphlet, and I was really nervous about it. There was so much pressure. But then they showed me a few reference images and asked me to do my best. I finally drew it and it ended up being printed the exact same way I sketched it. So that was pretty crazy to see my entire family have this thing with my drawing on it. And it eventually ended up being engraved onto my grandmother’s tombstone. So every time I visit her grave, my drawing’s there. That’s basically the story that locked me into being an artist.

But that didn’t mean I kept taking art classes. I didn’t actually take another art class for a year or two after that, until my senior year.

You went onto studying business, right? How did that happen and then when did you realise you needed to go back to art?

Yes, I was taking a lot of business classes in high school. When I was looking at higher education, most people advised me to focus on a business major. I got into the University of Colorado and started out in the business programme which I pursued for about three years.

At the same time, I was doing my minor in art elective courses. Gradually, I started leaning more and more into it and towards my junior year, I started to think about my own future and what I really want to do, and I started to get really bored and annoyed with business school. It felt really repetitive and stale. I also realised that I didn’t really want to work in an office anymore. I had an internship at a bank at the time. I didn’t want to do the whole thing of ‘graduate school and get a mid-level position office job’!

I started thinking that if I really wanted to be good/great at art and be successful in that, I have to fully focus on it. It has to become the main part of my life. I decided to just dive all the way in and start thinking about myself as an artist, and I finally switched my major.

You then studied Fine Arts at School of Visual Arts in New York. How was your experience there?

There were so many amazing things. It was great to have actual conversation and dialogue about my work with other students and professors. I remember for my first semester, I had an advisor called Fred Wilson, who is an internationally known artist. He actually had an opening at a gallery a week before our classes were to start. We all went to the opening and that’s where I met him for the first time, while fanning out a little bit at his show. Then we of course had interactions and conversations in the studio. Now it’s been almost four years since I graduated, so it’s great to see what my classmates are doing and which part of the world they are in.

With cardboard, I started to think not only about its brown colour, but also about how we describe cardboard as something cheap, something that’s easily replaceable or disposable. I guess my life as a black American has made me sort of empathise with that dialogue that I’m easily replaceable or discarded, and how even though we are almost all over the world, we are treated in a certain way, like we’re not equally human.

You are also a spoken word poet. We would love to know more about your music background? How does it influence your visual art? What kind of music do you particularly enjoy/listen to?

I always like to be around creative people and a lot of my friends happened to be musicians. I never learned how to play an instrument, so in order to be involved, I had to figure out something I could do (laughs). And I was like, ‘oh, I can use some words and I can use the microphone’.

So a lot of it was just playing around and collaborating with people I knew. I recorded maybe two or three songs for fun. I never took making music seriously. But in terms of the poetry aspect, I think there was a community in Colorado Springs, where I lived, called Poetry 719, where I did my first open mic. They were on campus and I was doing a project in my drawing class which was literally just me writing poems. I was looking at my handwriting, the four-dimensional aspect of turning pages, and reading it as drawing in a different way. When I saw this call for an open mic, I talked myself into doing it with this project. So that kind of started my spoken word poetry journey.

I would keep visiting that community; it’s very uplifting being around people that want to meet every week to just hear each other and share these incredible stories and creative output. There are people who just play the guitar, people who sing original songs, and people who share different types of poetry. There are people from all age groups too – you will find a 13-year-old who wrote something really thought-provoking and a 70-year-old sharing their creativity in the same room. That type of community spirit stuck with me because I hadn’t seen anything recurring like that. The therapeutic aspect also drew me towards spoken word, because it’s almost like group therapy.

Are you part of any such groups even now?

I don’t keep up with the circuit as much. Whenever I feel inspired, I just write something down. In New York right now, my poetry writing has spaced out a bit. I’ve gone on two or three years without writing much, but that doesn’t mean I won’t go to one of those jam sessions with some friends, where one friend is a great singer and guitarist, somebody’s the DJ, and then I’ll just grab the mic too. I’ll just play background vocals or something for the singer, and it’ll be fun. That’s how I keep that kind of going.

I still do write full poems from time to time, and I’ve published a couple. I have performed some of them at art shows too, and I think poetry can enhance and communicate with the artwork, when it’s up in spaces like that.

What are the genres of music that you enjoy?

My favourite genre is R&B. There’s a lot of emotionality involved in the music. R&B can be fun, it can be sad. It can take you through a gamut of emotions, but it’s never cliche. It kind of sits in this mainstream underground sort of atmosphere.

I really love rap as well. But I find that R&B singers can rap too, so a lot of times, the incorporation of the two is more my speed. It’s meditative at times too.

I want to start off with your most recent project – Black Fathers Matter – which is a project for you to show black men/fathers in positive images. How has your experience been of creating the project? Could you also talk a bit about the making of the project – you have used a combination of forms for this including photographs?

The project started in 2019. I was just looking for some reference images for my drawings. Initially, I wasn’t even sure what the exact topic would be, but I found myself being inspired by black dads around the city – just hanging out with their kids outside. And I started looking for a body of work that I could reference for black dads in the city and found nothing. Then I started to really just keep my eyes open in my daily life. As I would travel in the tri-state area, I would just observe fathers being fathers in any environment, whether it was a park, or the subway, or a store. You would just see dads being dads. At the same time, I found very few examples around me of just normal black masculinity in family life. A lot of my previous work deals with the negative portrayal of black people in the media. Essentially, what I was trying to do with this project is contribute more images to the positive side, more examples of what black men really look like. They are just living; there’s not a character plot all the time. It doesn’t always have to be dramatic or have some kind of an interesting story.

The project tries to counter a lot of stereotypes about black men – a violent, menacing sort of stereotype that is perpetuated in American media. And in the street, they use the word ‘thug’ a lot when they reference black people. There’s a type of oeuvre that is aesthetically asserted on black people in mainstream media and even in art history.

That’s another reason why I create in the style that I do, which is sort of a Western tradition of figurative realism, because the black male perspective or black artists’ perspective is left out most often. And there’ve been countless artists but one of the few we can probably name are maybe Jean-Michel Basquiat, but there were many before him. People might pull up Romare Bearden maybe, but even he isn’t quite as celebrated as other masters of art till this day. I don’t remember him being talked about in art school. Kerry James Marshall is taught in art schools maybe, because he was contemporary.

So anyway, basically, I’ve been taking photographs of fathers that I see around the area for the whole year and continuing. In the first part of the series, I stuck with the idea of using them as reference images. I was drawing the full figures and sort of commemorating the moment that was happening or just the fact that this exists – this black father, this time, this memory that’s occurring here. I actually grew up without my dad in the household, so this was a moment of growing up as a black male looking outside at other black men in a way and sort of went back to my own childhood in becoming a black male. So there’s a lot of duality involved. But in the second part of the series, I decided to use the photographs as more of a primary part of the composition. I essentially mounted the photographs that I printed out onto the cardboard substrate, so now the cardboard and the photograph are one object.

I remove the areas where the fathers skin is visible, and I redraw it so it’s still actually charcoal drawing. I cut out certain parts of the photograph and redraw some of the shadow with charcoal and do a lot of different aesthetic details. I think the tearing away of the actual photograph is tied with how the cardboard speaks to the environment. It connects with the nature of being black in America; this torn, rough existence; and yet these everyday moments still have to occur.

Black Fathers Matter

Essentially, what I was trying to do with this project is contribute more images to the positive side, more examples of what black men really look like. They are just living; there’s not a character plot all the time. It doesn’t always have to be dramatic or have some kind of an interesting story.

When did you start working with cardboard and other found objects? How does the form (especially of cardboard) lend meaning into the work?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I started using cardboard about ten years ago. It was me trying to use an alternative medium, something separate from a traditional canvas. I was trying to think about more material considerations and what the material actually means. And I started to think about, well, what if I combine something that’s brown already with my figurative work. My first thought was to use wood panels, but then I was thinking about what the history of wood panels means and what I would be sort of going into. Also, there’s an artist, Whitfield Lovell, who is already doing some amazing work with charcoal on wood panels, and he was actually an inspiration I looked at early on when I looked to cardboard as my alternative medium.

With cardboard, I started to think not only about its brown colour, but also about how we describe cardboard as something cheap, something that’s easily replaceable or disposable. I guess my life as a black American has made me sort of empathise with that dialogue that I’m easily replaceable or discarded, and how even though we are almost all over the world, we are treated in a certain way, like we’re not equally human. The reference I’m trying to apply is that of cardboard not being a valued material asset. If you think about even its use in industries, it’s pretty much used everyday, all over the world. It’s revolutionised shipping. And all of these things have parallels to the black American experience.

So I applied a lot of nuance about the material to the work. I was also thinking about it in terms of being in New York, and how even homeless people have these street signs on cardboards and you see cardboard signs on which you write your statements in protests all over. It’s a street and protest material, with all those other associations that I started to make with it. So then I simply started working on the compositions and how to either draw attention to the material or do different things in different projects to specifically talk about that connection. It’s all intrinsically there, just more emphasized in different ways.

On one hand, a lot of your work including ‘Police Cross Lines’ and ‘Criminalized’ are direct portrayals of the violence unleashed through police brutality on black people. On the other hand, you have also been trying to create “images of positivity, strength and nurturing” – especially through Black Fathers Matter. How do you create this balance? Is that a very conscious decision?

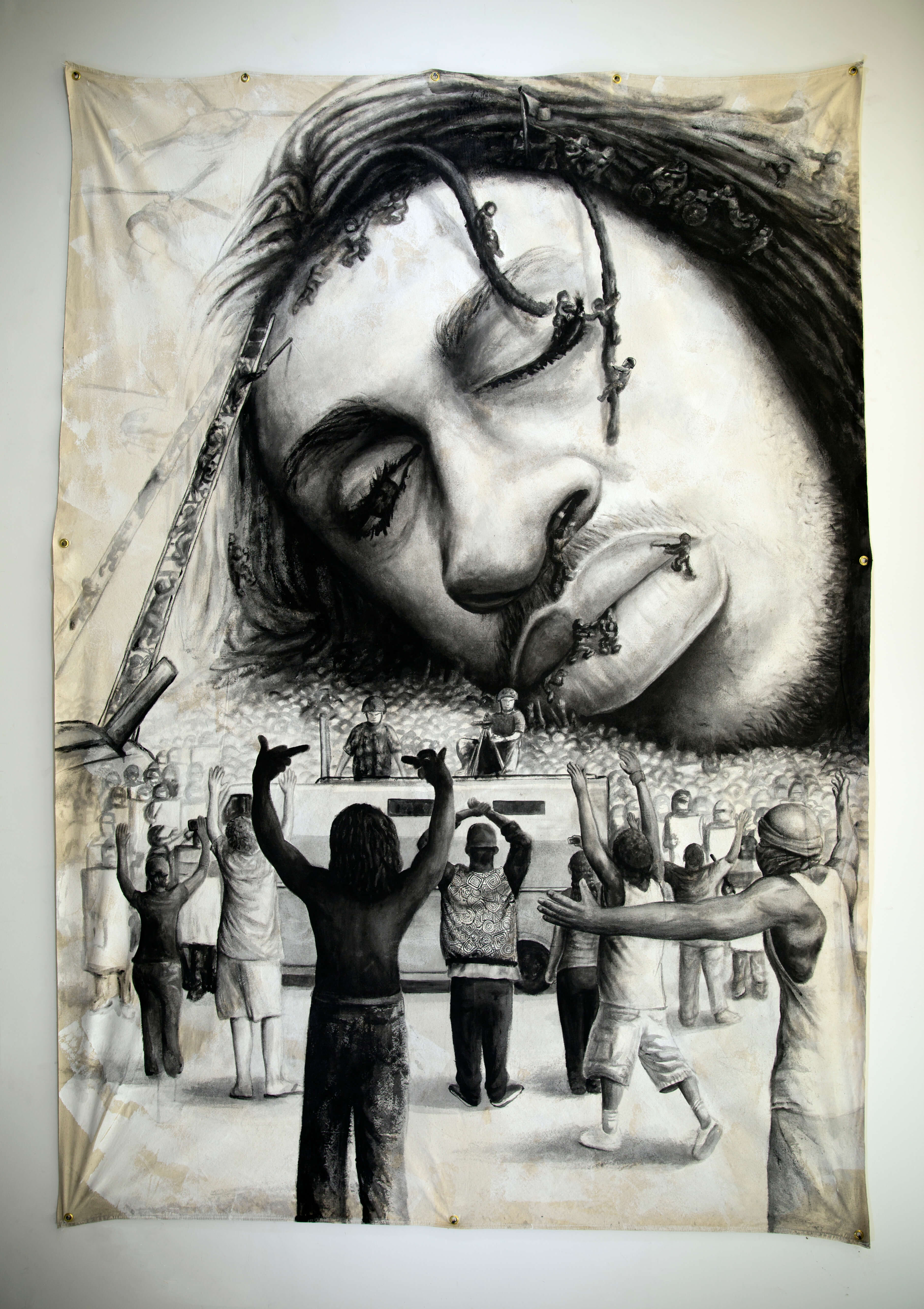

Yeah, it’s definitely a conscious decision for me. About a year ago, I was getting ready to do a project that was probably slightly more in your face than the ‘Police Cross Lines’ series. This was the ‘Our Angel’ series for which I’ve just made a couple pieces so far.

But I have a very strong narrative that I knew was going to make my work be perceived in a certain light without certain considerations being made. I also noticed, like I said, the lack of an existing project that I could reference for positivity about black fathers. I’ve seen some projects that deal with negativity like Titus Kaphar’s project about his dad who was incarcerated. It was a brilliant project. So I had seen different styles of that, but not in a way that I would appreciate seeing it in the world. A part of my motivation is to create work that needs to exist. I make work that I think I haven’t seen yet, but it’s an idea that should be represented. It’s weird to say but it’s like you notice there’s a hole or a void and if you have the ability to articulate or create the thing that would fit there, you should try to do that.

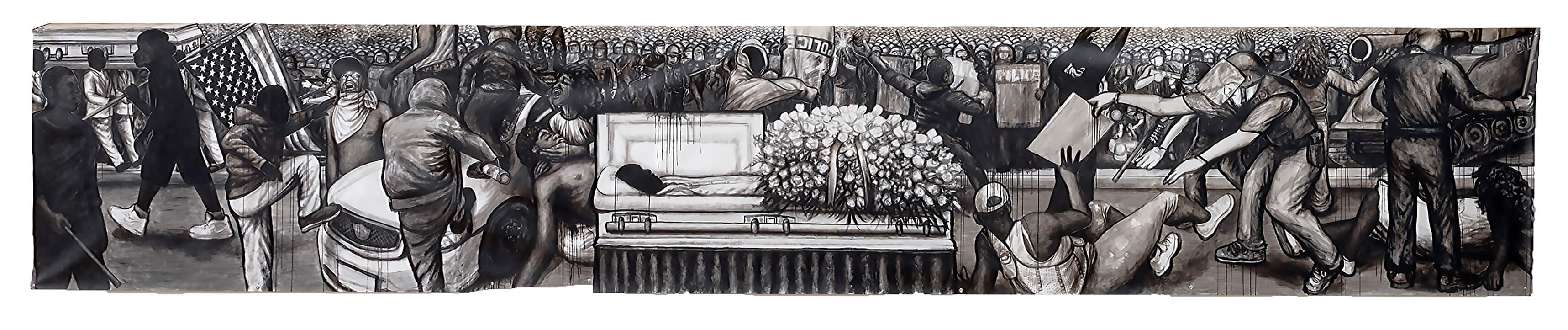

A lot of my previous work about police brutality was really trying to bring awareness and keep the conversation going. Because the ‘Police Cross Lines’ and ‘Criminalized’ series started in 2014 and 2015, which was five years before the times we are in now when we’re actually globally talking about it. We weren’t protesting a year ago when I decided to do more positive images. I knew that by continuing to create images where black people experience harm or violence, I was also inevitably contributing without some sort of balance. I wanted that when people look at my body of work in totality, they see the message I’m trying to send, which is that love is the most powerful thing. It’s really about empathy. The violent images are about me trying to instill empathy in people who don’t necessarily have it for those types of situations. To almost ask them – how can you not see this violence as excessively unnecessary?

And beyond that, it’s also about why don’t we see more images of normal black people. It was almost counter to what I was doing, where the news seemed to overly perpetuate images of black men in crime or being killed, a lot of that started to come up more in the media. And as a black male, that can become depressing. That’s part of why I created the ‘Police Cross Lines’ series in the first place, with that media depression I was feeling. So the positive part is trying to take me out of that media depression a little bit and hopefully, also capture the times and the way black men and fathers are presenting themselves in the world. It’s almost a time capsule in that regard.

Police Cross Lines – From Ferguson to Baltimore

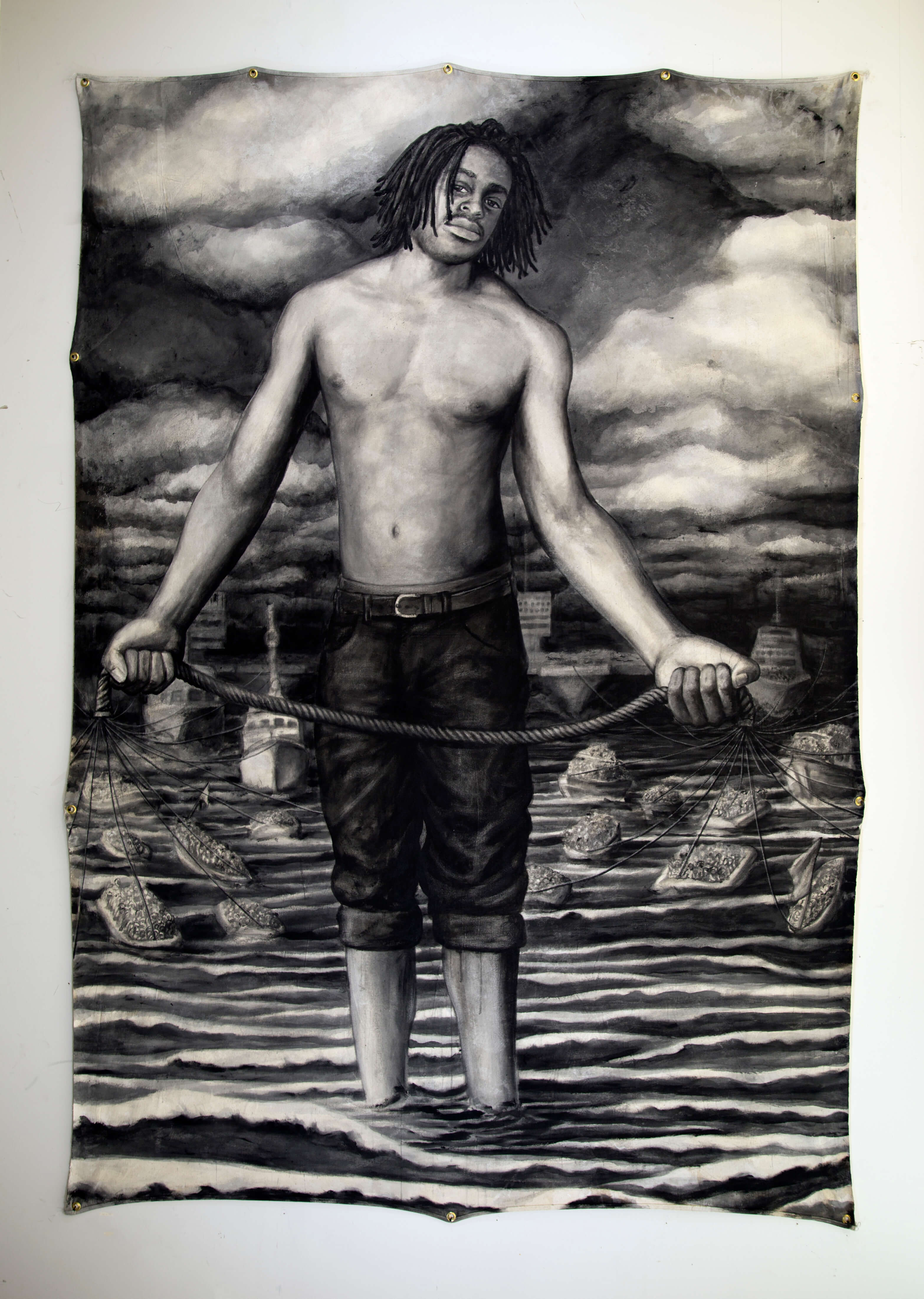

In ‘Black is the Giant’ project, you have inserted yourself into your artworks. Could you talk about the inspiration behind that project and the idea of placing yourself in the artworks?

The ‘Black is the Giant’ series was actually my thesis project in graduate school. And the idea stemmed from a lot of those feelings I was talking about before about the media’s over presentation of black death, and sort of making black men fear the police more. It felt like deterrence in a way, like the media was trying to do some sort of fear tactic. But basically, the anxiety starts to build up even if you think about micro-aggressions and just being in spaces where you’re reminded of your ethnicity, and you think about why you’re singled out as the other.

All of those occasions build up and build up, and I was thinking of that build up eventually becoming giant, and essentially becoming a Giant. All this repression towards blackness made ‘Black is the Giant’, so it’s a pile, a Giant, essentially coming to fight against that type of energy. I tried to create narratives where I’m the Giant – a combination of repressed emotion, stereotypes, and micro-aggressions.

I live out this fantasy in ‘Refugee and Reinforcements’ piece where I could save somebody in war or in a famine. I take them somewhere and bring what they need. There are so many conflicts, like I had a friend who died in Syria, and there’s just a lot of things you can’t really talk about. So that was a way to talk about that.

There is a piece called ‘We Stand Together in Brooklyn’, which is inspired by Goya’s work ‘Colossus’. It’s also inspired by the gentrification at the time. I was talking about that sort of coloured otherness, minority groups protesting against being pushed out. And then there is a piece called ‘We Came Together in Washington’ which I made about a year before the Women’s March in Washington. So it almost felt like I predicted it, and that was cool. It has the giant pointing at the Washington Capitol, and a couple of angels whispering in his ear and a bunch of stormtroopers floating in parachutes.

Wake of the Giant

Refugees and Reinforcements

I also wanted to know about the idea of angels in your work – especially in the ‘Subway Angels’ and ‘Our Angels’ projects.

My original reason for wanting to incorporate angels was the fact that in our history, black or brown people are left out of that visual narrative of cherubs and old depictions of Christianity, and the art history’s dominant representation is Christian art. And as a black American, Christianity has a lot to do with our history here. Whether or not we’re Christian, but we have a connection to it based on how the country was created and exists today. By using angels, I’m protesting the fact that there aren’t that many black angels, and that should be normalised as well.

In the series ‘Our Angels’, the piece I am currently working on references a wounded angel. I am changing the narrative and modernizing it. Essentially, there are a lot of parallels in terms of the Bible and the black American story – the tales of redemption, the chosen ones, and the suffering – all of those things are eerily similar. They’re almost like the stories of the time.

Slave owners were considered good Christians, and there’s a lot of history involved in that. My objective in the next project is to show the dominant Western religion, and protest elements of it while using their language of Western art history. And rendering all of that, I’m not only inserting the black narrative, I’m sort of correcting a perception of if. If it eventually gets put into the history books, then it changes the context of everything.

Our Angels

What are some of the things that really bother you in the media portrayals of black people, especially in the last couple of years?

There are a lot of odd things, not just in the media but in the world, that race gets used for.

Even a few months ago, before the presidential debate started in the USA, the candidates were essentially using the black community almost like in a competition to get the black vote. They ignored what the leaders of the black community said in terms of what they would like to hear from those candidates, and instead just pushed their own agenda about how they’re building relationships with black people. Then in one of his addresses, Joe Biden said this controversial statement: “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump then you ain’t black”. It was an off-taste joke that would have probably worked like 20 years ago, but we’re in different times, and it’s not cool. And then it adds to other things like voter suppression is part of the media, and that’s not even on purpose, but it just becomes a part of the narrative where the other candidate responds and does something else to show how cool they are with black people and that’s at the government level.

And then you see these protests about Black Lives Matter have reignited. Even though the Breonna Taylor situation happened in the first week of the quarantine, we didn’t really hear anybody really speak about that situation until George Floyd happened three months later. So the media cycle is opportunistic, and it takes what people sort of buzz toward, but it doesn’t actually try to provide you information in real time. It paints information in a very specific way. So it’s really interesting to see how the verdict that was given for Breonna Taylor recently where the police officers were charged with the endangerment of the neighbours, but nothing to do with Breonna Taylor and her family specifically. And how the NBA and other sports platforms which have been using Black Lives Matter and names of people like Breonna Taylor to push initiatives, don’t talk about the verdict when it comes out. They were very vocal about “social justice”, but they don’t provide their opinion on certain situations. So it starts to look inauthentic. So those are the moments I guess, especially recently, where it’s kind of been annoying.

You have often mentioned in your interviews that one of the aims of your work is to dispel misunderstandings about black people and to evoke communication. In what ways do you think about the impact of your work? To what extent do you get involved in reactions and conversations around your work?

I really think a lot about the reaction. My personal belief in terms of creating work is to anticipate the audience a little bit, and even differing audiences. There can be a target audience, but I consider niches of whoever could possibly see the work and then decide for myself whether the certain decisions I’m making and how they could be construed is acceptable for me, and how I would respond to that being presented.

I don’t necessarily get confrontational if someone thinks something completely outside of how the work is intended to be presented. Because it often is, in my own self, an expected vantage point. And it provides me with an awareness of the type of viewpoint these individuals are coming from. For instance, certain pieces that are more in your face and violent evoke different reactions. And I’ve talked to people about them. I’ve seen someone cry after looking at a piece and then telling me about the impact of the imagery and what it means to them. And sometimes, there’s been negative criticism including that I have glorified certain aspects of police brutality and their authority.

And it’s interesting to see all of this play out in real life. It’s almost like being a scientist, and basically, I’m going through the scientific method to test something, and the last step is to find the results – which is to see if people perceive it in the way I thought it could be perceived. When I talk to them, it’s also a way to understand my ability to have foresight when I’ve made certain choices. So I look forward to people getting upset after seeing an artwork, if that’s what I have intended. I’m glad if someone cries because I might have cried in the studio trying to evoke that type of emotion, or found this information for the first time, and now I’m trying to reinterpret it. And that’s a good feeling because it means that I’m making these emotions translate.

I used to often ask artists in my interviews earlier whether they believe in art for art’s sake or art as a means to try to change the world, but I feel it’s no longer even a choice. With the way almost the entire world is going right now, I feel it’s imperative that artists get more and more involved. How do you feel about this? Do you see your role as an artist getting even more crucial in the times to come?

Being an artist is really hard. Artists are so self-conscious and not very confident. They’re always second guessing themselves, thinking that they could have done better, and I guess that’s how they end up making great stuff. But at the same time, they don’t realise the power and the type of culture they’re creating and the things that trickle into pop culture and people’s everyday worlds.

One of my favourite artists, Nina Simone, said this in one of her interviews – ‘An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.’ And that’s what I feel – it’s my responsibility to talk about what’s happening in the world through my point of view. And if I am not representing what I want to represent, it might not get represented at all and there will be no information about it in the future. So I try to contribute in my own way to the historical context of just being a black American.

Art for art’s sake is important, but the artists would still need to consider the cultural implications of how thinking in a certain way contributes to the conversation of art making. So it’s good, but it shouldn’t be done without considering the world. And you can, of course, focus on your spatial and material considerations and make those primary, but you shouldn’t be blind like ‘I’ll just do my own thing’. The interpretations of audiences and how that might contribute to your work – whether you like it or not – is important. If it’s an overwhelming sentiment of interpretation, whether you do it on purpose or not, for art’s sake, it’s the resolve. So you have to also be willing to be aware and consider those things.

A part of my motivation is to create work that needs to exist. I make work that I think I haven’t seen yet, but it’s an idea that should be represented. It’s weird to say but it’s like you notice there’s a hole or a void and if you have the ability to articulate or create the thing that would fit there, you should try to do that.

2020 has also been a globally horrific and crucial year because of the pandemic, among many, many other things of course. How has the pandemic/lockdowns specifically affected you and your work?

It’s felt like we have had three or four years in this one year! We’re turning into the last quarter (which feels like a whole year) of our crazy 2020.

I’ve been trying to just keep the positivity going. If I focus on the negative things, it could be one of the worst years of all time. There’s the covid situation. My fiancée is Iranian, and there was a lot of stuff going on with Iran this year and that was even before the pandemic started. Then during the pandemic, layoffs happened and then the Black Lives Matter protests. But even then, instead of focusing on all the negatives, I have decided to focus on the positivity.

I had a residency that finished in February at the International Studio & Curatorial Program. That’s where I developed the second and third part of the ‘Black Fathers Matter’ series. That’s the crux from which most of that work came. Then I was in a major museum show called ‘Tell me your story’ in Amersfoort city in the Netherlands. It was a survey of Black American art over the past 200 years, and it was great that I got to be a part of that show. It had so many icons. I’ve got a bunch of other shows coming up too. I also had an online show with a platform that I contribute a lot to – Living Life Fearless. I am also curating my first show for the platform as well. It’s an all-women show with works by ten artists. And I just started teaching online for the School of Visual Arts’ undergraduate programme.

So a lot of good things have been happening actually. I’m still getting opportunities and I’m still working on new projects. You just have to take it one step at a time. You got to wear your mask when you’re in proximity to others, keep your hand sanitizer, and just be safe. But aside from that, just try to live normally – the new normal.

Apart from Covid-19 vaccine, what are some of the things you are looking forward to in 2021?

Well, I’m looking forward to a lot of things in 2021 actually. I’m going to be in a group show (with 2 or 3 other artists) at Kent State University. I believe it’s based around the ideas of fatherhood. I will also continue to work on the ‘Our Angels’ series. I am still adding a couple of more pieces to the ‘Black Fathers Matter’ series. So I’m really excited about making more of that work.

We’ll walk slowly and see where the summer lands. Oh, I am also going to get married in 2021 so that should be pretty cool.

Dáreece's photograph is provided by him. ©

The cover image is from Dáreece's project 'Police Cross Lines'. ©