I am attracted to people who were born into circumstances that were meant to crush them, but they fought against the bullshit of the world.

An easy way to describe artist and writer Molly Crabapple’s work is to say it’s radical, political, courageous, and extremely powerful. There is a constant quest for truth and for adventure – however excruciating the circumstances may be – that can be traced through almost all of Molly’s life. To get a glimpse of this, we highly recommend reading her outstanding memoir, Drawing Blood, to start off with.

Molly is also the author of Brothers of the Gun, an illustrated collaboration with Syrian war journalist Marwan Hisham. Her reportage work has been published in The New York Times, New York Review of Books, The Paris Review, Vanity Fair, Vice, The Guardian, The New Yorker, and Rolling Stone, among many other publications. She got massive acclaim for her first project as a journalist sketching the frontlines of Occupy Wall Street. She then went on to cover (with her words and art) Lebanese snipers, labor struggles in Abu Dhabi, Guantanamo Bay, the US border, America prisoners, Greek refugee camps, and the ravages of hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. As an animator, she has worked on a new genre of live-illustrated explainer journalism, collaborating with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Jay Z, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and The ACLU.

For this interview – our last of this year, based on the theme of ‘Resistance’ – we talked to Molly about the pandemic, New York, social media, new projects, and how she picks her battles. The interview was done over an audio chat in July 2021. Read on:

Molly Crabapple. Photo by Marina Galperina.

How have you been through the pandemic, Molly? What has your experience been so far?

Oh my god! I think before the pandemic hit India this year, New York was probably the worst hit place in the world. I have been in lower Manhattan in New York throughout the pandemic. I left the city only this June to go to Greece. In March 2020, it was a horrible scenario – every single day I would hear sirens all the time, taking our neighbours to die in the hospital at every possible hour. I think you can relate to it since India also had a similar situation.

New York is always filled with people, and to see the busy streets of New York completely deserted was like a scene right out of an apocalypse movie. Many small businesses were shut down because there wasn’t any relief for them. So many immigrants were left impoverished by the pandemic. I tried to help my city by volunteering and delivering food to old folks. I also cooked many meals for the free refrigerators that broke and homeless people use to get free food.

But at the same time, it was a strangely beautiful moment as well. New York has suffered from a plague of extremely rich people who view the city as a consumption experience. They have built hideous luxury high rises, stuffed their houses with slick, expensive crap, and kicked poor and working class people out of their homes. But when the pandemic hit, all these rich people fled the city – around 300,000 people left, mostly from the richest zip codes. It was a strange moment. Though New York was suffering, it became a city for its own people after these rich people left. There was misery and death, but there was a sort of anarchic beauty to it that still partially exists. However, I’m quite sure that the government is going to eliminate that pretty soon. They are already cracking down on working class youngsters who have been enjoying public spaces in a way they didn’t before.

Before we go ahead, I just want to give my biggest solidarity to India. I have a lot of friends there. And my heart fucking breaks for what happened there.

For an article titled ‘Life and Death, But No Trash Pickup: Diary of a Young COVID-19 Nurse’ for ProPublica

Portrait of artist Caroline Caldwell while quarantining in New York’s famous Chelsea Hotel.

You have often spoken about your habit and need to make lists for everything, ever since you were a kid. I am curious to know what kind of lists are these? Do you still make them?

I’m religious about them. As a kid, I used to make a list of everything that I wanted to be when I grew up and can finally shape my own life. The list had the biggest to smallest scales of ideas – from wanting to be an artist to having bookshelves filled with lots of books in different languages. I tried my best to do something out of them everyday, to make a step, however small, towards one of those goals. Whether or not I was successful is a different story (laughs). For instance, as a dreamy little 12-year-old artist, I wanted to live in Paris, so instead of doing my schoolwork, I would try to study French every single day. I never actually did learn good French, but it was my way of trying to prepare for a future I had planned for myself.

But now as a 38 year-old working artist, the list has become more prosaic – ‘Get this paper to do this artwork’; ‘do this gallery show’; ‘make sure the printer has enough ink’, etc. I make a plan of what I want to do each year, make a list of it, and break it into months and then days. I never finish my to-do list, but I do try to chip away at it. I make these lists in black and red notebooks, as I don’t trust the computers for doing them.

I was just listening to your Al Jazeera talk with Paul Mason and you both talked a lot about technology and its impact in that interview. Old internet also played a huge role in your life – you have mentioned some fascinating stories about that in your book ‘Drawing Blood’. Things have changed drastically now – social media comes with crazy amount of problems. Facebook as a company is so problematic. How has your relationship with social media evolved in the last few years?

I hate it, for one thing. However, my early career was shaped and enabled by social media platforms, especially Twitter. I owe a lot of my journalism opportunities to editors noticing me on Twitter. When I got on Twitter initially though, it had a straight timeline view, but now most social media platforms – I think all of them – have gone to algorithmic timelines, which means that the AI decides which posts you see and what your followers get to see.

In my opinion, these algorithms, especially on Twitter, are optimised for conflict. I am going to talk mainly about Twitter because I am most familiar with it. I have never liked Facebook, and Instagram is cool but I mostly use it to look at pictures of cats. The thing that gets people most addicted to Twitter is fighting. If one person tweets that someone is a moron, a lot of people will like that tweet, and they will get a happy burst of dopamine. Then someone will call them out as a moron. It’s a cycle that gets people hooked on to the platform. Social media platforms want you to get addicted to them. They are like drugs in the sense that they can either up your mood or crash it. Sometimes, they act like performance enhancing drugs and sometimes, they can completely wreck you. I think Twitter is optimised for conflict because unlike other social media platforms, you can’t delete the replies posted by people. Trolls just harass famous accounts to build their own followings. The platform is especially set to make people fight, and that’s what I have hated about it.

In terms of what I have loved about it – I have met a lot of my best friends on Twitter. I also met the collaborator for my book ‘Brothers of the Gun’, Marwan Hisham, a Syrian journalist on Twitter as well.

Another important fact is that this idiot fight club has also been an incredible resource for people who have historically been shut out of major platforms. For instance, the growth of the Palestine Solidarity Movement in America owes a lot to Twitter, Facebook, Tik Tok, and Instagram. Historically, Palestinians have been shut out of a lot of large media platforms, and even when allowed, they were talked down to, treated degradingly, and even slandered. And because of these reasons, I can never be completely down on social media, even though it does some horrific things like making people waste their lives fighting, scrolling, and feeling anxiety.

So the experience is mixed. Social media is like the printing press and other major technological changes, in that it reshapes society with good and bad implications.

In its review of your book ‘Drawing Blood’, The New York Times called you “a new model for this century’s young woman”. It’s such a great honour but also a very heavy title to bear. You are an extremely well-known artist, so well respected in the media, and most importantly, many young artists look up to you. Does this responsibility weigh on you? Do you consciously think about it?

I am 38 right now which means there is a whole generation of people that was born when I was 20, so there is a generation which has grown up looking at my work. Many times, amazingly talented folks in their early 20s or late teens tell me that my work has inspired them to be an artist. My god! When is your heart ever more full except for when someone tells you that?

At the same time, I think that you can be inspired by all sorts of people, but the idea that there should be a perfect role model is silly according to me. I am immensely inspired by Pablo Picasso, but he was also a wife-beater and he left one of the earliest champions of his work to die in a Nazi concentration camp because he didn’t want to rock the boat with his Nazi clients. Picasso was also one of the greatest painters of the 20th century, and everyone – whether you like him or think he is a fraud – is creating work in an art world he helped shape.

I think you should allow yourself to get inspired by anyone you want to, but just because you love their art or their music or because they are super glamorous, you should not expect them to be a perfect person. As a group, we artists have more than our fair share of selfish bastards and delusional narcissists. So I feel that the only responsibility I have is to be a decent human being, and that’s everyone’s responsibility.

Portrait of Mohammed Tipu Sultan who was one of the organisers of taxi drivers protest, against the deadly medallion debt in New York.

Portraits of musician Kim Boekbinder, featured in DOPE Magazine, Issue 10.

You have spoken about depression in the past. We are going through a universal mental health crisis right now and I feel it’s more important than ever to discuss it. I would love to know how do you personally deal with it?

I will just speak for myself obviously. Luckily, I haven’t had a depressive bout for a while now. Thank god! For me, the discipline of doing difficult things usually helps me get out of feeling miserable. It may sound strange but studying Arabic has helped me remarkably. Arabic is a very difficult language, especially for English speakers. But it’s a language I love. In fact if I had nothing else to do, no talent, and if I could just be a lady of leisure, I would study Arabic all day and read contemporary Arabic literature.

Arabic diverted my mind from the feelings of doom and depression. Instead, I could focus on this beautiful, mathematical, rigorous language. It’s just like how many people usually feel better when they have a good run. This is a similar experience for my mind.

I may still not have developed healthy ways of dealing with these issues, but following these disciplines have helped me a lot personally.

You have mentioned in an interview – “The crushing speed of New York definitely influences my work, but conversely, I am able to find so many more opportunities because everything is here.” Is this how you still feel about New York? Do you ever dream about moving to one of the places that you have travelled to and really loved?

I think that New York is my home for the foreseeable future. It’s where my mother lives and all my friends live. But let’s say if I was starting my life on a blank slate, I could definitely think of a few cities.

Oh, I would love to live in Mumbai – it is the ‘Maximum City’ as Suketu Mehta called it. I love that place. I want to draw every single street there. It’s definitely one of the greatest cities I’ve been to in my entire life. I can live in Mexico city as well. I love Athens in Greece. Unfortunately, Istanbul now is not the same any more because of Erdoğan. But it definitely is amongst my favourite cities in the world.

New York now is different than it was before. Because it is one of the world’s biggest financial capitals, it’s also the place where all the repellant billionaire scumbags go to launder their money by investing in real estate. So every single day, you see these largely empty glass luxury towers which look as if hypodermic needles have been shoved into the body of the city. Things here are becoming more unaffordable, sterile and expensive. That was driving me crazy before Covid.

I just felt that everything that was human scale was being pushed out of my city. It’s an expensive city for everyone except for the millionaires/billionaires; no one else could afford to buy a house in New York, and even a tiny apartment is out of reach for anyone but the very lucky upper middle class.

Many rich people left the city during the pandemic and NY got a bad rep in the national media which demonised us for being hit so badly by Covid. It was being said that we got it because the city was dirty, crime-ridden, and had too many immigrants. But the city began to feel very different after all this happened. It became much more a city for its people, the people who loved it enough to stay back during the worst times. I love New York more than ever after this time. Sometimes, you love someone more when they’re sick. My hope is that after this horrific year of deaths we have had, we can build a city that’s for its people, a city that’s human, socialist, and not just a place for the world’s elite to stuff themselves up at fancy restaurants and have exciting, expensive consumer experiences.

Photo by Marina Galperina.

I think you should allow yourself to get inspired by anyone you want to, but just because you love their art or their music or because they are super glamorous, you should not expect them to be a perfect person. As a group, we artists have more than our fair share of selfish bastards and delusional narcissists. So I feel that the only responsibility I have is to be a decent human being, and that’s everyone’s responsibility.

Could you give us some details about your current projects?

Right now, I’m doing this really complicated mural project (update: the mural is now complete), for The Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural & Educational Center. The center is a Pureto Rican/Latino art space on the East side, named after the great Puerto Rican poet Clemente Soto Vélez. It’s an old school house which looks like a church.

I am creating a large mural for their first two rooms, and kind of playing with the architecture. I’m doing these detailed murals inspired by Clemente Soto Vélez’s poems. It’s a great honour, but a weighty one too. The building is historic and really beautiful, and the mural is going to be the first thing that people would see when they go in. I got to live upto it. That’s why I’m currently spending all my time painting leaves, barbed wires, lovers, rocking horses, and all of these different elements that will be printed in a big format and then collaged onto the walls. I’m going to cut out hundreds of little leaves, add them on, and then add paint. It’s an enormous, labour intensive work. I am very excited about it.

I am also working on my third book which is about the Jewish Labour Bund, which was a Jewish socialist, anti-Zionist, revolutionary political party that my great-grandfather was a part of. The book traces his life journey first as a young revolutionary and then as a painter, as well as the life of the movement. For this book, I had to learn to read Yiddish. I had never studied a Germanic-based language before and they’re very difficult, very different from what I’m used to. It also involved speaking to some of the coolest old people that I have ever met in my life. People in their 80s and 90s, who have these memories of this lost world. They are so cynical and witty. I have a friend, Marv Zuckerman, who I have interviewed a lot. He is a wonderful singer, and he remembers all these old, revolutionary songs, and can just sing them off the top of his head. I feel privileged to have met these people. I have been working closely with my mother for this project since she was very close to my great-grandfather, and both of them are artists. In fact, he taught her painting. We both have been rummaging through boxes full of old papers and photos. I have spent hours decoding crumbling bits of archives, trying to figure out the world he lived in. So that’s another project I am working on, but I am doing it so slowly that my editor is going to come and beat me with a stick until I finish writing to make my deadline (laughs).

I’m also working on a new series of articles about the way Covid has reshaped New York. This is for a group called ‘Economic Hardship Reporting Project’. They fund work related to poverty. They have given me a grant to develop a series of articles on the divides between rich and poor, and how the lives of both groups have changed since Covid.

Esos Arboles artwork at The Clemente Center

There is so much happening in the world right now. How do you pick your battles and subsequently, the subjects for your art and journalism?

I think in some ways Covid has forced most people to make their focus a lot more local, since travelling was restricted. In a way, you were forced to pay attention to what was happening around you. For instance, during Covid, I became really concerned about what was happening with renters in New York. In New York, being a renter is more unifying than any other category, including gender, race, or anything for that matter. 70% of people stay on rent in New York which is an overwhelming majority and the single biggest group you can belong to.

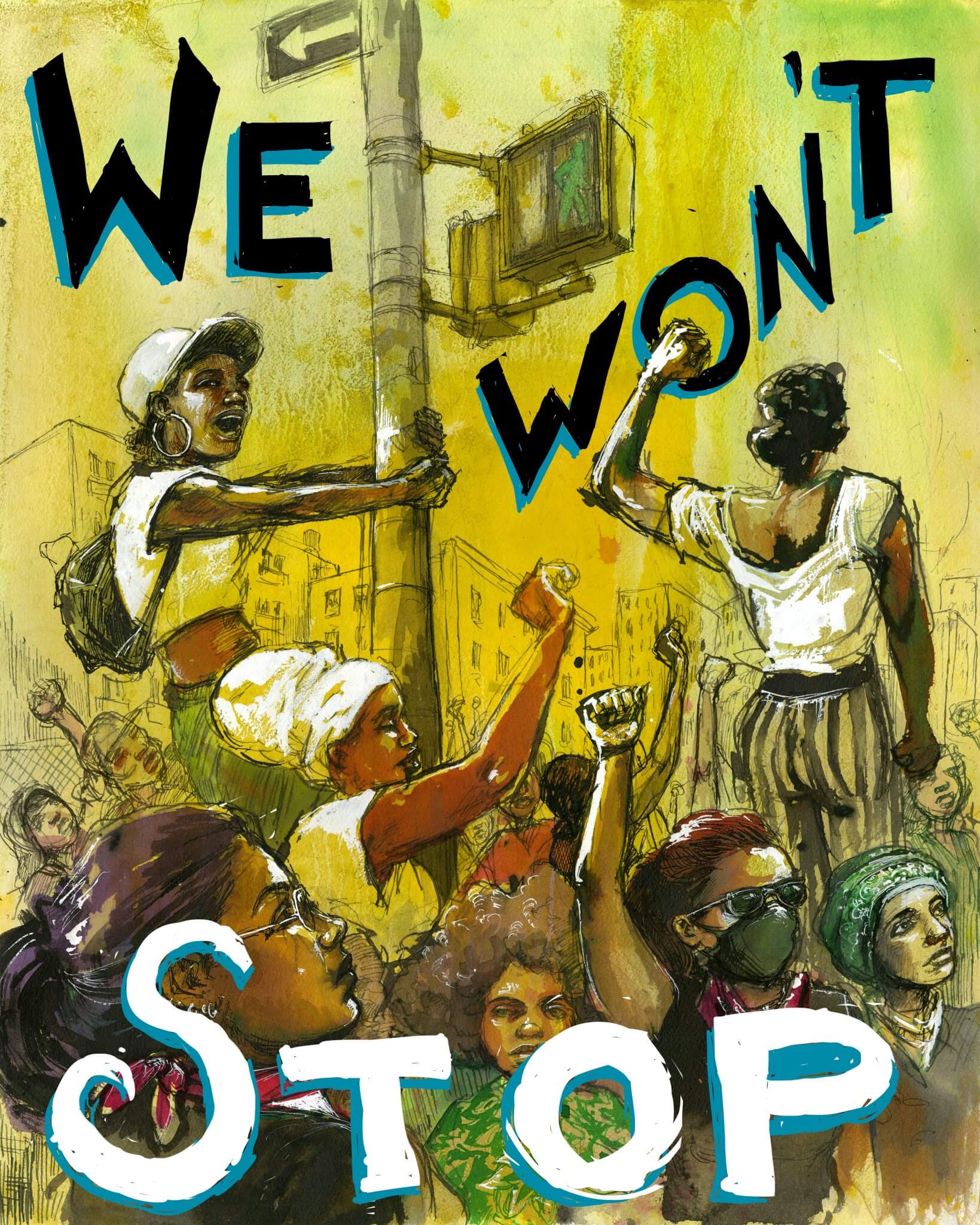

And essentially, all renters are getting screwed, even the ones who have money, because even if you have money, it doesn’t mean you want to spend all of it on a place which maybe has rats or where you can get kicked out on a 30-day notice. Since Covid, so many people have been out of work, and in the beginning it was very hard to get any aid, so a lot of people were at risk for getting evicted. I got involved in a movement called ‘Cancel Rent’ in New York City. I created various banners and art for them. We won a huge Eviction Moratorium under which landlords were not able to evict people for over a year – though there were many loopholes.

For me, as a person who is a tenant in NYC and wants to stay here, the battle for normal people to be able to have housing is very important. People who aren’t rich – poor, working, and middle-class people – have been forced out of the city centers all over the world, not just in NYC. The city centres are becoming these luxury parks that the affluent elite have taken over. It is important to fight for the rights of these people to stay in cities regardless of the amount of money they earn. This fight is personal for me.

In terms of how I have chosen stories in the past, I am attracted to people who were born into circumstances that were meant to crush them, but they fought against the bullshit of the world. One of the most interesting people I met in the course of reporting was a young South Asian man who lived in the Gulf and used to serve tea in one of the big construction companies that build cities in the Gulf. The society there was so racist. People couldn’t imagine that a South Asian working class man in Abu Dhabi could be brilliant. He could speak a bunch of languages. He was sharp, perceptive, and soon he started getting out information on labour abuses to every single Human Rights organisation. He helped me with my Vice article. This young man was born into a world which assumed that because he was poor, came from South Asia, and worked in the Gulf, he was just a machine to build fantasy worlds for other people. But he said, ‘I am not dumb. I am not an animal. I can see through these lies and bullshit, and I want the world to see it too.’ And so he made the world see it.

I like to write about such people. I love the story of a smart rebel.

Molly’s advice for young artists who want their art to be political and want to be actively involved in the critical issues that surround them – EXCLUSIVELY IN OUR ‘RESISTANCE’ PRINT ZINE. COMING OUT SOON.

‘Our Lady of Liberty Park’ from the series Shell Game

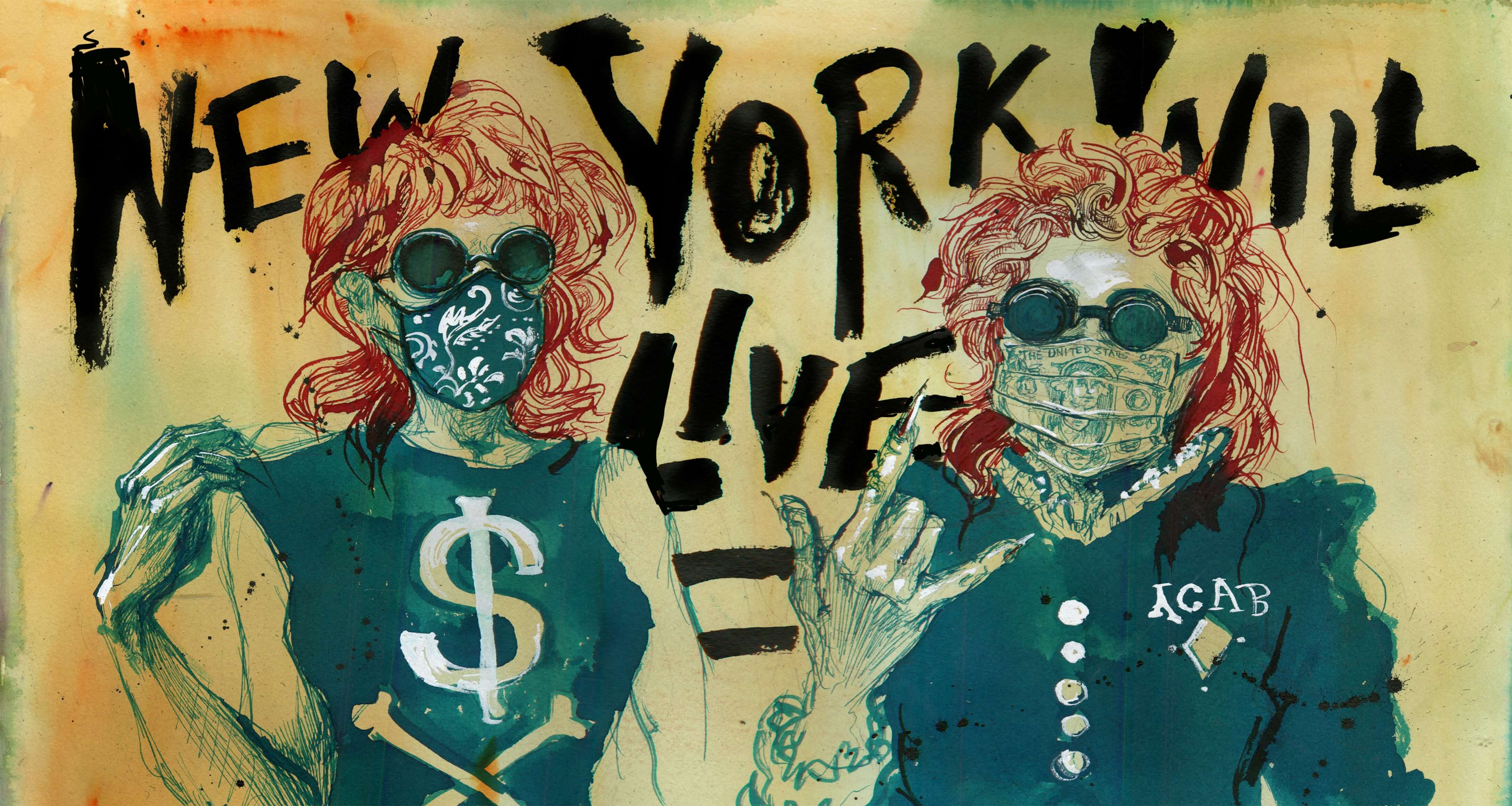

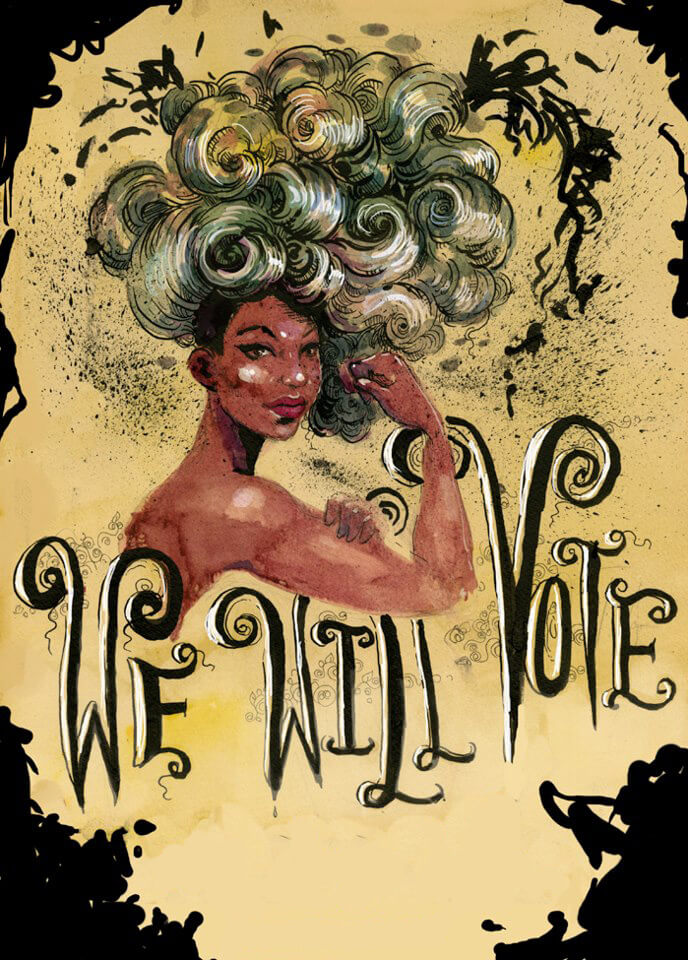

Artworks by Molly Crabapple

Molly's profile image (edited to fit the format) on top is by Marina Galperina. ©